“Our methods of design are often burdened with the exigencies of everyday life, which become the basis, inspiration and logic for creation. This logic structures the imagination for creation of space, where the everyday reproduces itself – a fictional provocation helps in altering the logic to focus on the exploration of space beyond the everyday.”

— Rupali Gupte

I want to begin by opening up the trope of the ‘Unbuilt’ in architecture. One may need to distinguish the ‘Unbuilt’ as the ‘Not-Built’, often due to various logistical issues, such as a lack of funds or a falling out with the client – as against the ‘imaginative’, ‘projective’, or ‘fictional’. This essay uses the trope of the ‘unbuilt’ to discuss works that fall in the latter realm of the imaginative – or more accurately, the fictional – and discusses its various uses.

In his essay ‘The Significance of Fictionalising’1, Wolfgang Iser tells us how in literary fictions, existing worlds are overstepped – and although they are still recognisable, they are set in a context that defamiliarises them. In doing so, fiction becomes a means of actualising the possible. This is the reason that human beings, in spite of their awareness that literature is make-believe, seem to stand in need of fiction. Quoting Sir Philip Sidney, the English Renaissance poet who challenges Plato’s claim that artists lie, Iser argues that the poet doesn’t talk of ‘what is’ but of what ‘ought to be’. For instance, there are many literary works that not only put together an alternative imagination of the world but also make a sharp commentary on the prevailing sociopolitical conditions.

In Sultana’s Dream2, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain invokes a feminist utopia called Ladyland where men are kept in mardanas and women are free to move around in public spaces. This is a place where there is no need for the police and the military, and where women have created a land of plenty through engaging in science, art and philosophy. This literary work uses the device of humour to flip gender roles in an incisive critique of all that is taken for granted. It cleverly defamiliarises a context, to make us realise how we normalise situations, and to show us that other worlds are possible. In Begampura3, the 15th century poet-reformer Ravidas imagines a land without sorrow, without suffering and where all are equal. This poem and Ravidas’ imaginations subsequently became inspirations to many anticaste reformist movements in India.

Academia, just like literary fiction, is often accused of being a part of the ‘unreal’ world – as if the real world lies outside the academic space, in the world of the market. Architectural Academia, in particular, is often asked if it is adequately preparing students for this ‘real world’.

The discipline of architecture has had a long tradition of generating material that challenges the status quo, in pointing out the absurdity of what is normalised as the ‘real world’; the academic space in playing this role often presents a mirror to the world, opening up the possibilities of multiple realities.

From Giovanni Piranesi’s etchings to Étienne-Louis Boullée’s imaginary monuments, from Italo Calvino’s fictional cities to Franz Kafka’s distorted world—fictional works have provided significant provocations to not only question the existing world, but also to explore alternatives. Lebbeus Woods spent an entire career drawing architecture, taking us into spaces we had never imagined. His architecture was like scabs over the wounds of a war-torn city. John Hejduk, who built architectural installations like ‘the House of the Suicide’ and ‘the House of the Mother of the Suicide’, was once told by Eisenmann that his buildings are not architecture because one could not get into them – to this Hejduk rebuked that it was Eisenmann who could not enter Hejduk’s buildings because he could not understand or was not willing to understand them.4

My own foray into the imagined in architecture began with my work ‘Tenali Rama and other Stories of Mumbai’s Urbanism’5, an alternative history of Mumbai’s urbanism where the protagonist Tenali Rama receives a boon from Goddess Kali to become the wittiest person in the world; in return, the Goddess decrees that Rama should help build Tactical City, and that all his sons and daughters (with Rama becoming Rama for all female descendants) should be called Tenali Ramas, and they in turn should call their sons and daughters Tenali Ramas. In this way there are multiple Tenali Ramas all through the history and geography of Mumbai who help build Tactical City. The city’s history is hence structured in three time frames – the Colonial City (Mercantile and Industrial), the Socialist City (after independence) and the Global City (Post 90s); Tactical City generates a subversive architecture that proposes an alternative truant form for the city.

Fiction provides multiple imaginations and therefore opens up alternative possibilities, which is the key to any architectural process. Below, four uses of Fiction as a pedagogical process have been articulated; I shall illustrate a few of these with experiments conducted at the School of Environment and Architecture (SEA) over the past five years.

Fiction as a Design Provocation

Our methods of design are often burdened with the exigencies of everyday life, which become the basis, inspiration and logic for creation. This logic structures the imagination for the creation of space, where the everyday reproduces itself – a fictional provocation helps in altering the logic to focus on the exploration of space beyond the everyday. For instance, first-year students at SEA were given the fictional context of an old Chinese practice of making machines to punish loved ones. These were made by Chinese kings and queens to punish naughty princes and princesses, devised to ensure that their beloved children were not hurt but would remember the bodily discomfort enough to not repeat the offence.

Here, antithetical ideas of love and punishment came together to create bizarre devices that produce extreme situations of affects that the body would experience. For instance, one of the machines made the one punished move through a mazelike space, but always in sideways or crouching positions, producing bodily discomfort. Another one trapped the user into a tall space where the sky was so high up that it teased the inhabitant with an imminent freedom that was unattainable. A third device trapped the person within a fabric prison; the attempts at escaping would become a performance to be enjoyed by those trapping, as the fabric danced with every attempt. A fourth squeezed the person through a narrow red box only to discover the uncomfortably close visceral presence of human hair, which the interior was made of.

Gaston Bachelard in the Poetics of Space6 reminds us that the mind can forget but the body remembers – the fictional provocation was effective in not only charging the imagination but also sharpening the observations and experiences of the students’ own bodies. As they became involved in making the spaces, they became fully aware not only of the constraints of materials but also of the labour that went into their making.

Fiction as an Instrument to Defamiliarise a Context

Architectural sites are often trapped in their singular imaginations as loci of functions. However, in reframing the modernist trope ‘form follows function’ to ‘form follows fiction’, many learnings from the rich readings of a site can be drawn into the design process.

This process is seen in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities7, where unbeknown to the protagonist, the storyteller finds a multitude of ways to describe the city of Venice. The story evokes multiple scales of place, to be experienced by the individual body as well as by the collective. Victor Schlovsky in ‘Art as Technique’8 speaks of the role of art in defamiliarizing in such a way that ordinary and familiar objects are made to appear special. It is that aspect, he points out, which differentiates ordinary usage and poetic usage of language.

The second semester studio at SEA took students to several sites in Mumbai including Crawford market, Mulji Jetha market and Bhaucha dhakka to explore pedagogical methods that involve the translation of a text to space. Students wrote literary pieces about these places and imagined conversations in them, which they scripted as a play. They performed these plays with their bodies reproducing the experiences of these imagined spaces; the next step was to create a setting for these enactments in the college campus, to give them life beyond the moments for which they were created. Here, fiction pushed the boundaries of experience, which found its expression in the spaces designed. It is through fiction that the student becomes compassionate to various contexts and learns to overcome conventional readings.

Fiction as an Ontological Tool for Interrogating the Architectural Brief

Fiction can become a powerful tool to question the status quo in the articulation of architectural briefs. Michel Foucault speaks of the idea of the ‘normative’ as deeply implicated in questions of power structures. Pedagogical processes that ask ‘What Is _?’ can help challenge much of what we take for granted in the building of an architectural brief. By addressing questions of historicity – essentially, tracing genealogies of programmes – one can question their very basis and help chart out a more emancipatory future for the architectural programme. Questions of typology and spatial experiences can follow from these fundamental inquiries.

In the fourth semester at SEA, we ask an ontological question about ways of living that have been consolidated through architecture. These are questions asked about existing programmes, so as to open up debates around them. Fiction here is mobilised through challenging a conventional programme by asking a ‘What is?’ question about it. Instead of asking students to design functional types like schools or hospitals, we ask questions such as ‘What is a School?’, ‘What is a Home?’, ‘What is an Archive?’, or ‘What is a Clinic?’. The studio begins with fundamental questions about the nature of the institution posed by Foucault, focusing on the forms of power and knowledge embedded in the nature of these institutions. The debates in the studio then extend to how space plays a role in the construction of power structures. Studio projects go on to challenge these frameworks to then develop new programmatic types that address these questions and new spatial types that challenge the established codes of space-making.

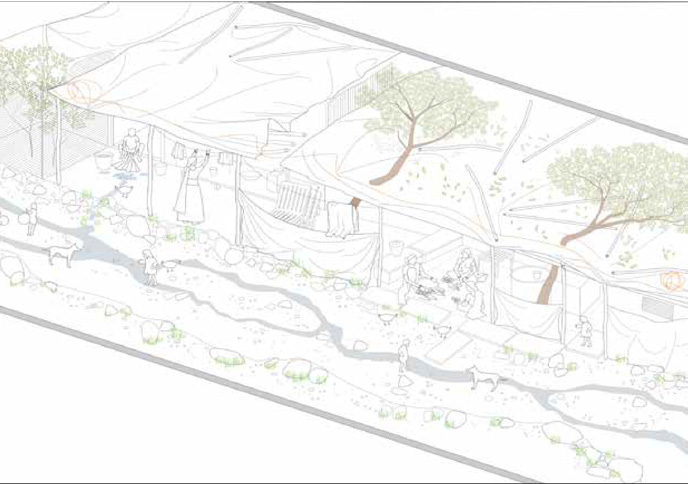

For the project ‘What is a home?’ students worked with ten sites in the eastern suburbs of Mumbai. Through intensive field work, they studied the idea of home in each of these neighbourhoods; they found that the idea of home in each case transcended the propertied notion of space that is often created through a techno-legal discourse employed by developers and housing rights activists alike.

For example, in the case of Bharatnagar, a resettlement colony in Bandra where houses were consolidated over the years, home was an assemblage of elements. Located next to Kurla, one of the biggest recycling industries in the city, the home became a kit of parts with various elements coming together to build the aspiration of a home in increments. In Shivajinagar, the home was seen as a set of incremental tactics. The projects that followed challenged the idea of how home is constituted – it posited a new idea of home, one that was made through multiple claims, through shared kinship relationships, through programmatic reimaginations, and through new typological inventions.

Fiction as Meta-Narrative

Fiction can also be used to splice together various observations, analyses and ways of reimagining the future (or past) to construct a meta-narrative that has the power to challenge the status quo. It can be an important process of scenario building, one which uses the device of semi-fiction to bring hard-core analysis and insights into a context and, in turn, propose an alternative future. Our own work at BARD Studio from ‘Tactical City, Tenali Rama and Other Stories of Mumbai’s Urbanism’, the ‘Chronicles of Ganga Building’, and Being Nicely Messy (a dossier for Mumbai to reimagine future Mobility) employed montage as a method to piece together seemingly disparate stories to tell a new story of the city.

Recently, fourth-year students at SEA, in an urbanism elective, put together the story of the contemporary spatiality of the city of Mumbai through a fictional murder mystery titled ‘Like A Regular Day’. They saw the contemporary city as constituting new kinds of entrepreneurs with new emerging work forms – and consequently new spatial conditions. The story followed the murder of an event planner, and his friend – a ‘fixer’, a man who has his fingers in many pies – who tries to find the murderer. Through this narrative, the story of the contemporary city in flux is told. This methodological intervention allows a playful but insightful reading of Mumbai’s rapidly changing urbanity.

To conclude, Fiction as a method is a rather underused tool in architectural pedagogy and practice. It has the ability, like literary fiction, to open up new possibilities programmatically as well as spatially. It also has the power to shake us out of our conventional normative ideas of architecture.

It locates the discipline of architecture within a larger space of cultural studies, rescuing it from the techno-legal space that it often tends to slip into. Fiction, as a tool to reimagine the ‘Unbuilt’, can fundamentally challenge the established ways of making space.

- Originally presented in 1997 as a lecture at the Learned Societies Luncheon in Irvine, California ↩︎

- Originally published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, Madras, in 1905 ↩︎

- Omvedt, Gail. 2009. Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anticaste Intellectuals. 2011 edition. New Delhi: Navayana. ↩︎

- Architecture Drawing, From John Hejduk to Eisenmann. n.d. Blackwood Production. ↩︎

- Archived in 2003 with the School of Architecture, Cornell University, for the M.Arch Thesis Program ↩︎

- First published in 1958 by the University Press of France ↩︎

- First published in 1972 by Giulio Einaudi Editore ↩︎

- Originally written in 1917 as an independent essay, later incorporated into the Theory of Prose in 1925 ↩︎