“I wanted to make a film that would give the people who took LSD at that time the hallucinations of the drug, but without hallucinating. I did not want LSD to be taken; I wanted to fabricate the drug’s effects. This film was going to change the public’s perceptions.”

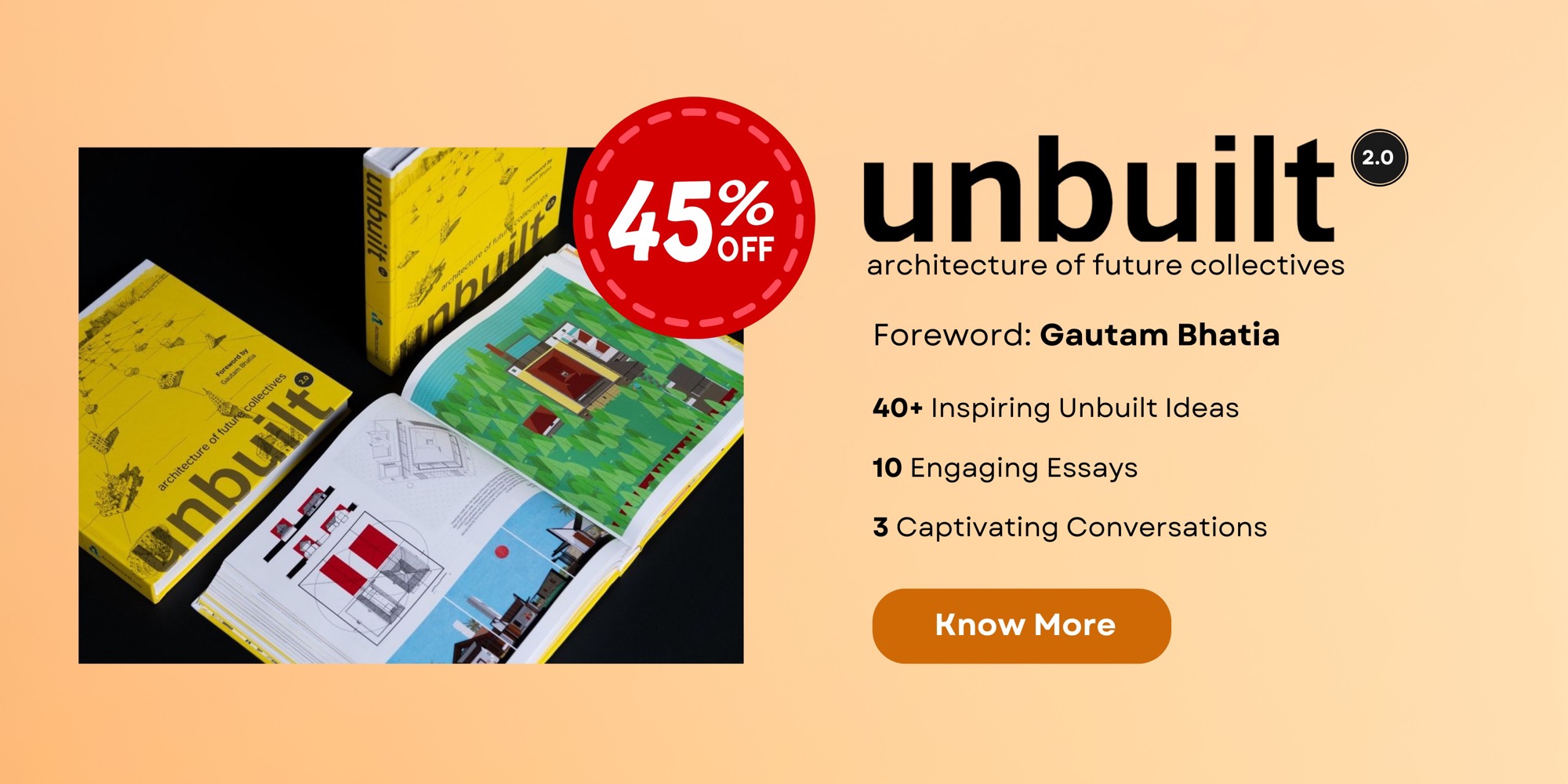

Perhaps no description captures the audacity of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s famously unseen film better than his own words in Jodorowsky’s Dune (2013), the documentary recounting his failed attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel. What survives is a one-and-a-half-hour portrait of the project that might have been – released years before David Lynch’s own adaptation, itself remembered as a critical misfire.

With a cast list only possible in dreams – Salvador Dalí, Mick Jagger, Orson Welles, and Pink Floyd – Jodorowsky’s Dune was too ambitious, both imaginatively and logistically, for Hollywood in the 1970s. “Maybe Dune had too much madness?” producer Michel Seydoux reflects in the film. “But a movie that doesn’t have a bit of madness is not going to conquer the world.”

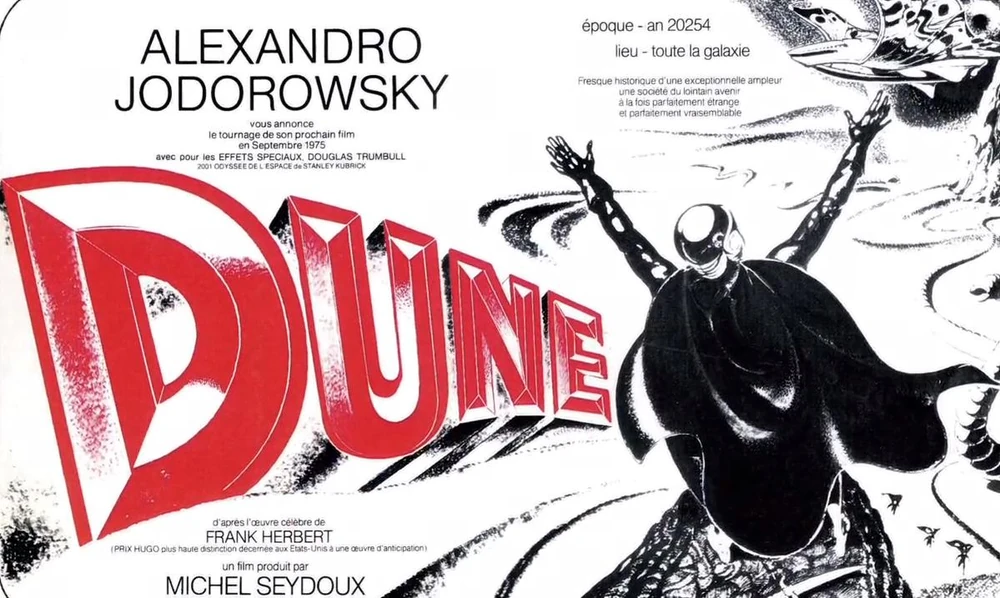

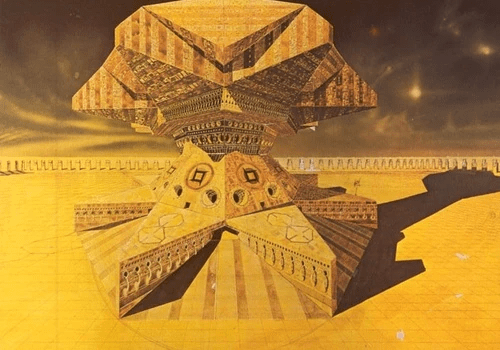

The documentary follows not only Jodorowsky’s fervent vision but also the creation of the fabled “Dune book,” an illustrated production bible that circulated through Hollywood offices, packed with storyboards, designs, casting notes, and technical plans. Like a ghost wandering the corridors of the industry, it left visible marks on later science fiction. Moebius’s storyboard of a desert hero entering a vast starship echoes in Star Wars’ opening shots; Chris Foss’s angular spaceship designs anticipate the look of Alien and The Terminator; and H.R. Giger’s grotesque sketches for House Harkonnen were directly repurposed into the biomechanical nightmares of Alien.

![Dune (unreleased film) H. R. Giger - [the strange power of unseen films]](https://unbuiltideas.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Dune-unreleased-film-H.-R.-Giger-the-strange-power-of-unseen-films-1.jpg)

Even decades later, the visual grammar of The Matrix carries traces of Moebius’s futuristic cityscapes. The dream team Jodorowsky assembled became some of the most sought-after artists in the industry, shaping the look of science fiction cinema for a generation. The disappearance of Jodorowsky’s Dune did not mark an end, but rather seeded a different legacy. This phenomenon of absence yielding unexpected influence re-emerges across film history.

Nearly fifty years later, similar tensions between ambition, absence, and influence resurfaced. In 2022, Warner Bros. Discovery shelved Batgirl after shooting was complete, citing a “strategic shift” related to post-merger cost-cutting. The film became a tax write-off; audiences would never see it, and its creators were left unsettled by the erasure. A year later, Coyote vs. Acme nearly met the same fate until backlash forced a retreat.

A new culture of erasure

“The system makes of us slaves,” says Jodorowsky in the documentary. “Without dignity. Without depth. With a devil in our pocket.” He then takes out his wallet, points to the cash, and says, “This money. This shit. This nothing. This paper has nothing inside.”

Not all unseen films vanish for the same reasons, and recognising these differences clarifies how absence functions in cinema. Some disappear because of corporate erasure: films completed and then deliberately withheld by studios for financial, strategic, or reputational reasons.

In these cases, invisibility is calculated, weaponised as a tax write-off, a portfolio adjustment, or an act of brand management. Others vanish through the fragility of archives: reels misplaced, stolen, or left to decay, where disappearance is accidental or the result of betrayal, and the absence that follows feels less like a deliberate or corporate choice than a cultural wound.

A third group consists of unfinished visions: projects that never passed beyond development or were abandoned mid-production, often because ambition collided with the limits of finance, politics, or mortality. Each type of disappearance produces a different ripple effect.

Corporate erasure reveals how finished films can be discarded; archival losses highlight cinema’s vulnerability to neglect or theft; and unfinished works show that even projects left incomplete can shape the imagination of what comes next. While the details differ, the common thread is that absence never remains empty.

Each form of invisibility leaves behind traces – storyboards, myths, rumours, or fragments – that shape the films that do reach audiences. Seen this way, the “unseen” is not a singular phenomenon but a spectrum of logics, each helping define the contours of cinema as we know it.

Censorship and politics: Asia’s unseen Cinema

In much of Asia, films vanish through censorship, political pressure, or cultural policing. These absences illuminate not only what is forbidden but what subsequently flourishes in the gaps.

In China, Zhao Wei’s No Other Love collapsed after a nationalist campaign, led by the Communist Youth League, against its Taiwanese actor Leon Dai. The loss did not simply remove a film from circulation; it reminded other filmmakers of the precariousness of casting and content choices under nationalist scrutiny.

Malaysia’s artist Namewee experienced something similar with Banglasia, banned in 2014 for “mocking national security” and promoting “LGBT elements.” Years later, after edits and political shifts, it was reborn as Banglasia 2.0. The unseen original shaped the seen sequel: every cut and change was marked by the absence of what censors excised.

India’s archive of the unfinished

India offers some of the most fascinating examples of unseen cinema.

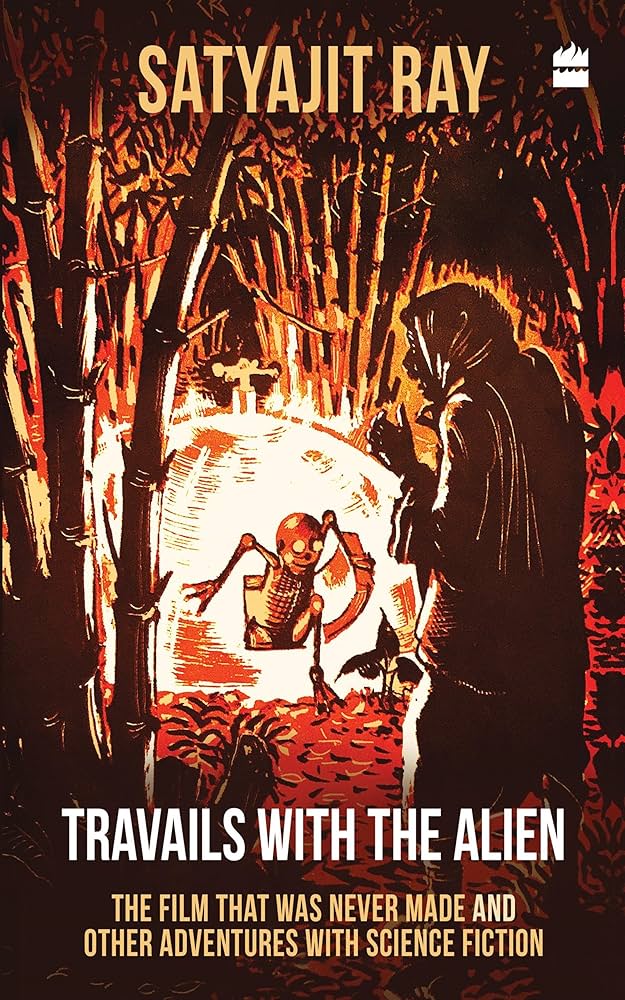

Satyajit Ray’s The Alien, planned in the 1960s as a Hollywood-India co-production, collapsed amid contractual disputes. Though never filmed, its script and notes circulated, and many critics later speculated that Spielberg’s E.T. bore uncanny similarities. Ray himself said that E.T. “would not have been possible without my script of The Alien being available throughout America in mimeographed copies”. True or not, The Alien’s absence fed a conversation about ownership and originality that shaped global perceptions of Ray as an auteur.

Kamal Haasan’s Marudhanayagam is another legend. In 1997, Queen Elizabeth II inaugurated the project – a historical film about Muhammad Yusuf Khan, an 18th-century warrior, with great fanfare. Lavish sets were built, footage was shot, but financing evaporated. The film was set to become the most expensive Indian film at the time, with a proposed budget of 80 crores. Haasan has periodically expressed his desire to revive it, calling it “unfinished business.”

In 2017, he said of its revival, “I need not only the money but also a powerful distribution network from the west to take hold of it and release it properly because it is an English, French, Tamil film. That is the virtue of the film, and it has to be done like that.” Its absence has become part of his persona, symbolising ambition thwarted by the realities of South Indian cinema economics.

Shekhar Kapur’s Paani, a dystopia about water scarcity, lingered in development for years before being shelved. Kapur has described the experience as “like losing a child.” Its absence, however, underscores how Bollywood has struggled to support speculative, politically charged projects – shaping the dominance of safer genres and IP-driven spectacles.

Singapore and the poetics of loss

Singapore, too, reveals how absence shapes presence. Tan Pin Pin’s documentary To Singapore, With Love was banned in 2014 for “undermining national security.” Ironically, a film about exile was itself exiled, its absence becoming central to debates about state narratives and cultural memory.

Then there is Shirkers (2018), a documentary about a lost film shot by teenagers Sandi Tan, Jasmine Ng, and Sophia Siddique in the 1990s. What was to be Singapore’s first road movie became the story of stolen original reels by the teens’ American mentor, Georges Cardona, and hidden for decades. The documentary reconstructs that absence into a new work—one critics hailed as among the most original documentaries of the decade. In this case, much like Jodorowsky’s Dune, the unseen film became the raw material for another, arguably more powerful, film.

Singapore’s “lost cinema” demonstrates how absence can itself be generative. Bans and betrayals not only erase but inspire: they create secondary works, critical debates, and archival rediscoveries that shape how a nation understands its own cinematic history.

Filmmakers on the unmade

Many filmmakers themselves have spoken openly about their unseen projects, giving voice to the weight of absence. Guillermo del Toro has often discussed his many unmade projects. Omnivore, in the early 1990s, would have been a surrealist claymation film, but all the puppets made were destroyed. That pain pushed him to make Cronos, his first feature film. About his history of unmade films, he has said, “I can get into a deep depression for a long time when a film doesn’t get made. Sometimes it almost takes you out!”.

These testimonies reveal that absence becomes part of authorship: the films that directors never made or never released still shape the films they do.

Absence as influence

The paradox of cinema is that the unseen is never entirely silent. Jodorowsky’s Dune was never filmed, yet its aesthetic infiltrated decades of science fiction. Paanch was never released, yet it influenced the rise of Indian independent cinema. Shirkers was stolen, yet it birthed a celebrated documentary. In each case, absence reshaped presence.

For artists, unfinished work can redirect careers or force aesthetic reinvention. For audiences, lost films cultivate a culture of curiosity and scavenging—searching for leaks, storyboards, or documentaries. For institutions, the question of preservation looms: should archives hold and eventually release films their makers or owners wish hidden?

Jerry Lewis’s infamous The Day the Clown Cried, about a circus clown imprisoned in a Nazi concentration camp, was never released but donated to the Library of Congress in 2015, with the caveat that it was not to be made available until June 2024. In September 2024, a documentary on the film aired at the Venice International Film Festival, and in May 2025, Swedish producer and actor Hans Crispin claimed he stole the only copy of the film. 45 years after the film was never released, Crispin’s action evoked a discovery, now in a bank vault. This timeline of the holocaust comedy time and stewardship can transform even suppressed films into historical documents.

The unseen also functions as a critique. Every banned or cancelled film points to the boundaries of the permissible – whether those boundaries are financial, political, or moral. In doing so, the unseen shapes the contours of the visible.

Ghosts

Cinema has always been haunted by these ghosts. These absences are not trivial footnotes. They shape industries, redirect careers, fuel myths, and define the limits of cultural expression. When a film vanishes, it leaves behind not silence but influence – shaping the stories that do reach us. The critical question is not only which films get greenlit, but which completed works are allowed to exist.

If visibility is currency in the digital age, then absence remains one of cinema’s most powerful forces. In the end, what is unseen does not disappear; it lingers, shaping the imagination and future of film in ways that presence alone never could.

Feature Image: H. R. Giger’s concept for the Harkonnen lair. This design was notably reused in the “Alien” franchise. Source: Wiki Fandom