I don’t know how to accurately characterise un-built projects. Should they be seen as designs that got rejected, or as designs that helped build the capacity for future projects? There are as many (if not more) unbuilt designs in an architect’s archive as there are built ones; the unbuilt ones bear the advantage of not having passed through the heartbreak of implementation, where most of the idealised characteristics of the design are compromised.

Whichever way the reader sees it, SHiFt’s experience with design competitions has come to define the way we regard unbuilt designs within the practice, best embodied by our work for the Gujarat Energy Development Agency’s campus in Vadodara, Gujarat.

This came to pass in January 1991, a particularly cold winter. The national competition consisted of two stages, and we had qualified for the top five—information that we received when our office was snowed in with a lot of work. Around November 1990, when we were announced as finalists, I decided to forego working on this project as it was unlikely to be built, but six of my colleagues had other plans. They ganged up and phoned all our clients at that time, asking for a month’s leave, especially for me. Of course, all the clients were very accommodating (architecture is a slow process after all). This conspiracy was revealed to me around Christmas 1990, and I was told that (a) I had no reason to claim that other work was dragging me down, and (b) we had only 20 days to the date of the submission, so I had better get down to it!

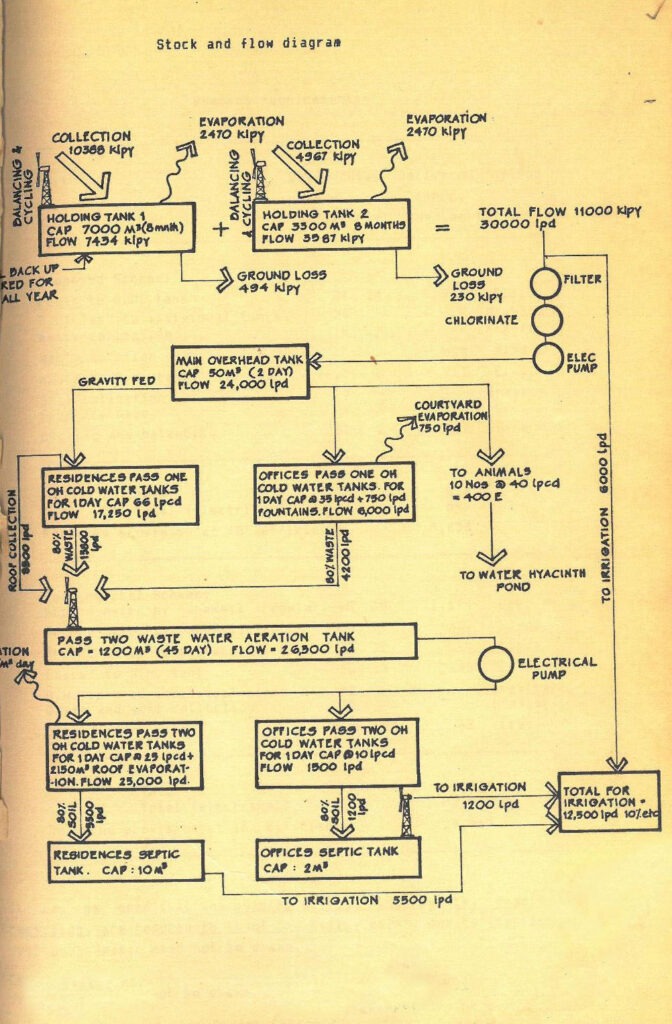

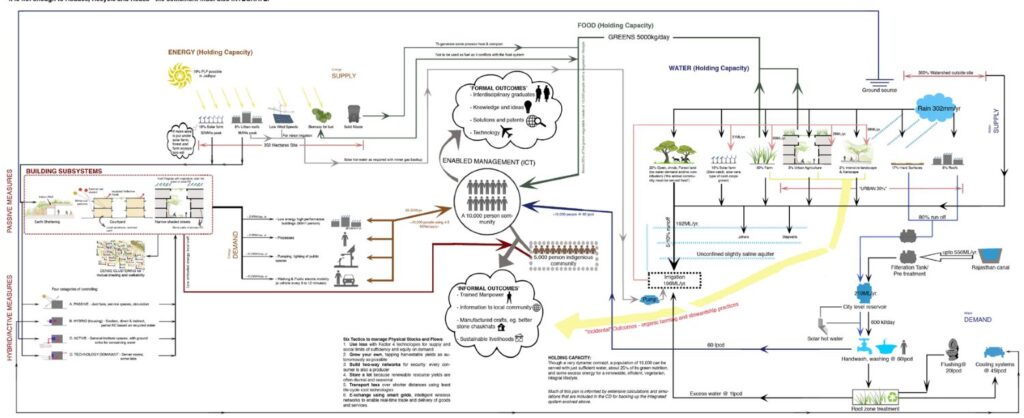

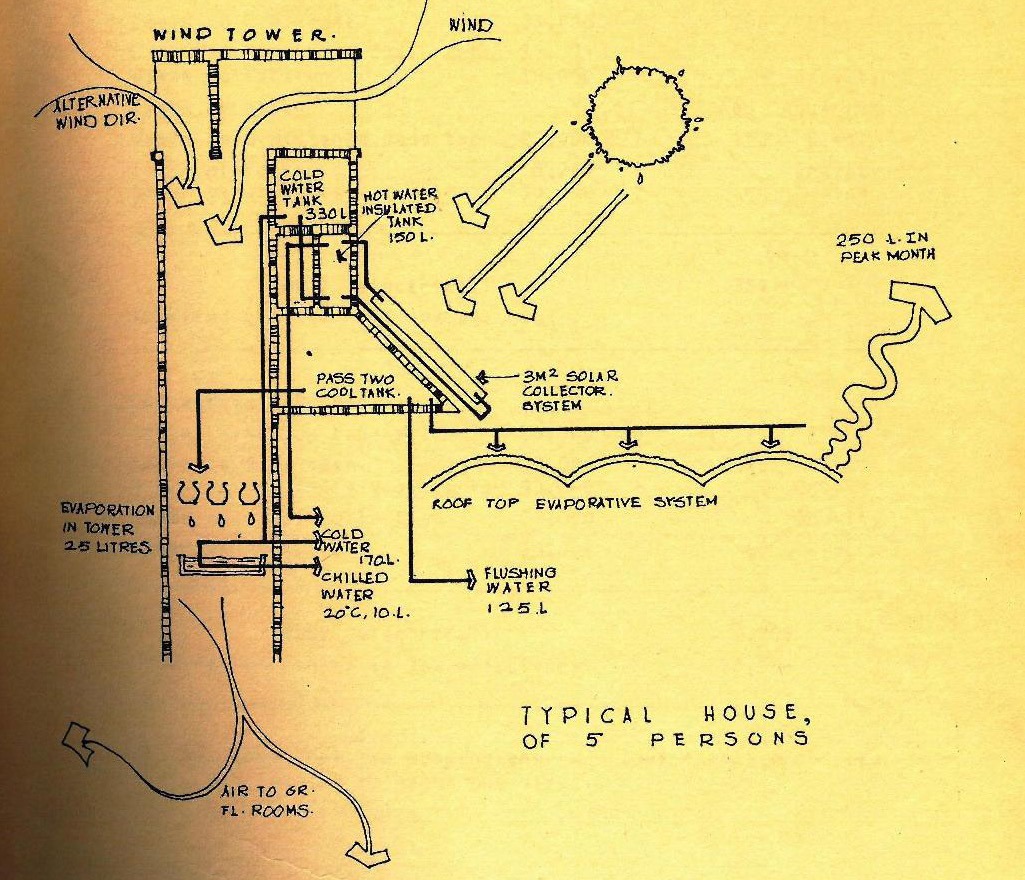

Central to our design thinking was a schematic representing the flow of water—a theme that in 1991 was somewhat avant-garde. We prepared this schematic from scratch, using a large drawing board, pins and strings—the water system design was then converted into a detailed, quantified diagram which became the centre-piece of the master plan. There were a large number of other sub-systems that tied in with this framework, such as the evaporative cooling system, which used treated recycled water to modulate ambient temperature in various buildings.

There were a large number of specialist consultants that were involved in working out parts of this complex scheme: daylight, construction, plumbing, electrical, thermal, and even horticultural; it was my task to ensure that all these parts came together without inconsistencies, and worked together, aesthetically and practically (that is what an architect mainly does: assemble specialist pieces into a coherent whole, like the director of a film). I did this the only way I knew: by spending much of the 20 days either awake or available to be woken up whenever a piece of design or calculation came into the office.

This technique ensured that there was one design, not a pastiche collage of ideas. This technique, called a ‘slog’ (and a related one, called a ‘charrette’, where a team of technologists work together interactively and continuously to create a design on a deadline—typically waking up in the last 24-48 hours—bringing their multiple perspectives to the project at hand), remains one of those techniques that are not easily taken over by Artificial Intelligence, and makes me believe that I shall be gainfully employed even after the accountants and scientists and mathematicians and managers have lost their jobs.

Partly due to the slog and the consequent originality—and also due to the jurors’ and the director’s appreciation of our due diligence and computations, and in retrospect, their foresight—we were announced the winners after the usual delay of a few months. We were delighted, of course. The initial delay was to be expected, a common occurrence in government circles as the people announcing the results are not sure which senior official might object, but a few more months went by after the announcement, with no news at all from the Institute.

Finally, we got a call from the Director—he needed us to come to Vadodara to circumvent the bureaucratic slowdown. Unfortunately, I was not knowledgeable about getting my waitlist #1 ticket converted to at least an RAC, and as it turns out, the director had a weak heart; even as I returned from the railway station in Delhi to my office and called him to delay the meeting, I was informed that he was no more!

It came as no surprise when a few weeks later, the whole scheme unravelled. The Institute soon changed the basis of the design, and therefore negated the competition. They did, however, pay us the prize money and soon went on to appoint a couple of local architects to do parts of the project, now broken up into a separate residential component and an office, located on different sites.

Twenty-eight years later, and in hindsight, I feel that perhaps the design was too early for its time. The technology wasn’t ready; realistically, we could have ended up with waterproofing, plumbing, and even electrical problems. These were times before Net-Zero Energy projects or Smart Grids were called that, and we were attempting to implement an intelligent ‘living’ campus—one which displayed a metabolism like that of a living organism, where all aspects of the campus affected all others, just as it happens in living beings. The analogous comparison with a biological system may sound far-fetched, but if you scratch the surface, it is not difficult to see that evolution and resilience are outgrowths of complex systems where every part relates directly or indirectly to all other parts—somewhat like large cities, as well as living organisms.

In December 2012, we got an opportunity to design a campus again, this time in Rajasthan. The two-stage competition for the master plan for IIT Jodhpur was just as gruelling as our previous endeavour; the task was too large for a boutique firm to do it alone, and the ecosystem of architectural design had changed in the meantime, so we went ahead with a large consortium consisting of our little firm, a large global multi-national planning and infrastructural firm, a large India-wide sustainability analysis firm, and a boutique environmental design firm, quite a bit like ours. It also meant more slog—but this time, there was also a charrette, so my natural inward reluctance towards working long hours alone was somewhat mitigated by the presence of my colleagues. It also helped that we were living in the information age, where bits of the design flowed over cyberspace and communication happened over mobile telephone lines and through SMS.

If nothing else, the high speed of information flow allowed us to work across disciplines and geographies (the work was conceptualised in the Netherlands, Delhi, and Bengaluru, simultaneously). If one compares the two schematics, it is easy to see that they are analogous—separated by time, access to technology, and most importantly, the nuance of application. Our principles were honed over 22 years (unconsciously and possibly in hibernation, through many smaller projects); for IIT Jodhpur, we proposed to build with the desert rather than against it. And so we created the same schematic in disguise 22 years later, now in an updated form – except instead of representing only the flow of water (which was mainly what we did in 1991) this time we conceptualized the flow of energy expressed through myriad moods and colours, water flows in 5 different purities, mobility flows, food flows and people flows as well.

This is now a much more complex organism, and therefore that much more resilient and realisable! Finally, after about 27 years, the original schematic has come to life with the IIT Jodhpur Campus’s first phase being built. I suppose one cannot call it an unbuilt project any more – or can we still call the Vadodara campus unbuilt and this one built? And was the Vadodara campus hence better, because it was not implemented? For this last question, I am of the opinion that the unbuilt project was, at least idealistically, much better. Perhaps the best way to look at this is to think of projects like Vadodara as unbuilt prototypes which lead to the built example in Jodhpur.

Of course, Jodhpur has many teething issues. Will it meet the challenges that we sought to address in 1991, as a renewable energy campus managing on very little or no resources? Almost definitely no. Will it meet the aspirations that we had in 2012 instead, with a specific site and brief? An honest answer would be: several of them, yes.