In a series of projects by Gautam Bhatia, the designs expand on the limitations of seemingly predominant sensibilities and propose an elastic idea of architecture, discrete projects that explore different approaches to public and living spaces. Within a conceptual energy that leads to the visualisation of new spatial scenarios, it becomes a commentary on and an enquiry into a socio-culturally embedded vision of these archetypes. Simple, perspicuous ideas emerging from a process and enquiry, these proposals take on a more elastic view of the status quo and represent the notion of an architectural ideal as much as ambition.

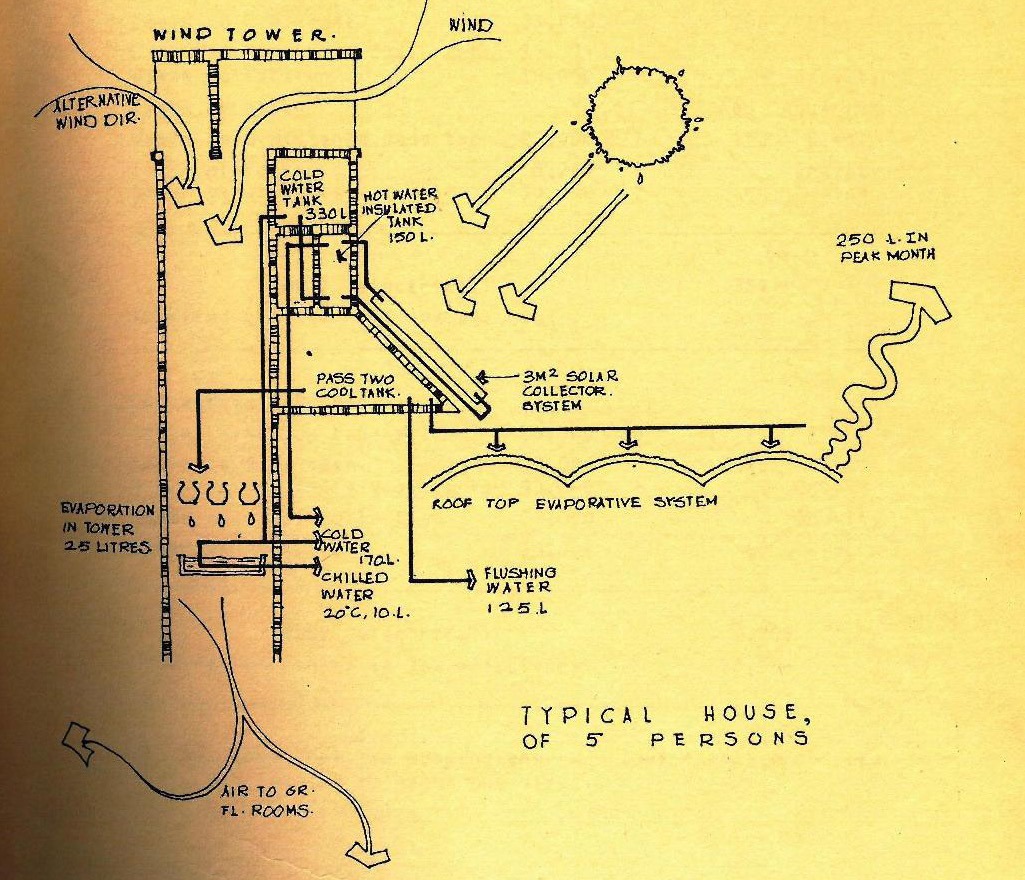

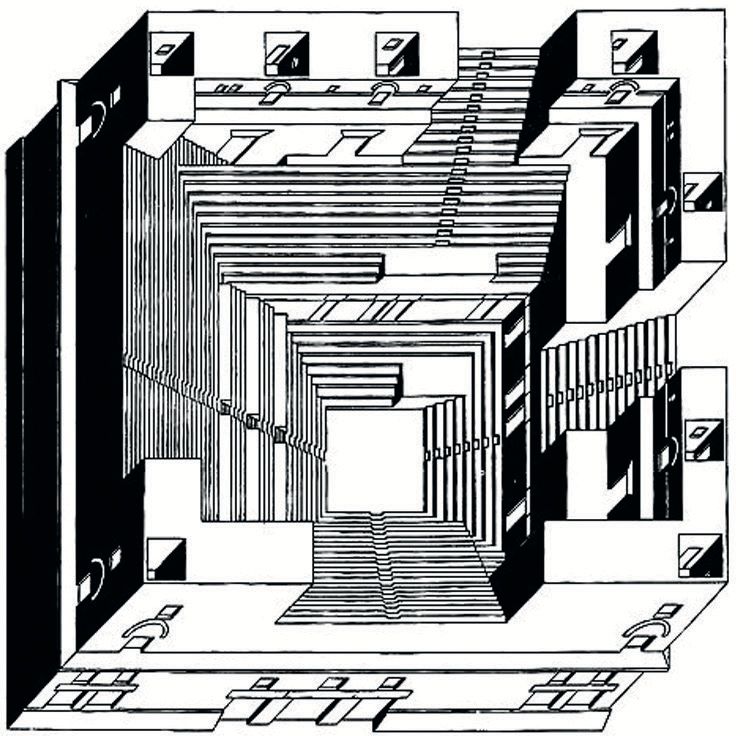

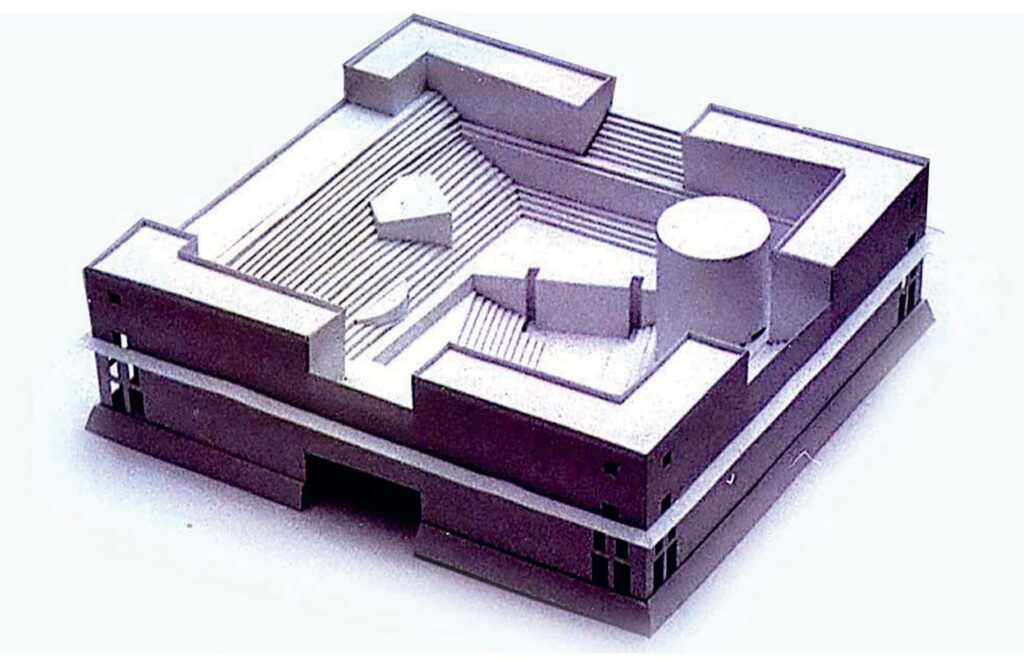

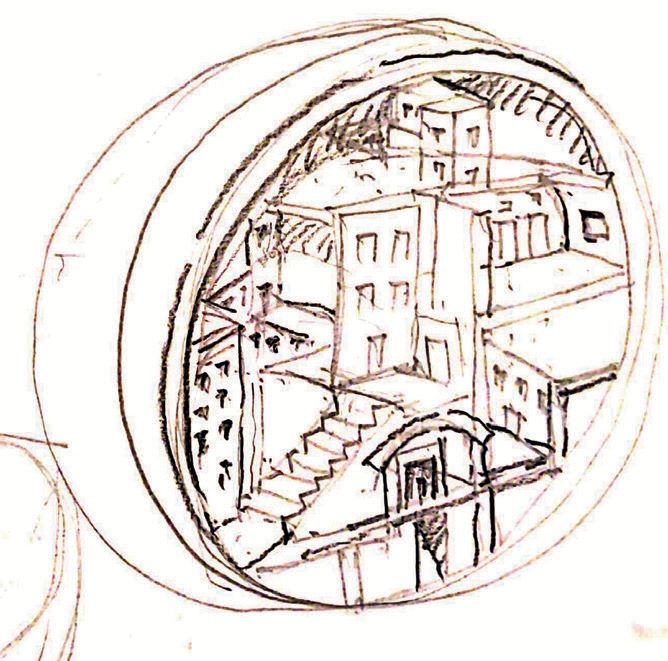

Bharatendu Natya Akademi, Lucknow

The site – given the trend of the city’s rapid development – was likely to become part of a dense urban area, and a cultural institute would get absorbed into a mixed urban fabric — part residential, part commercial, part office. The loss of identity was an important condition that determined the singularly unified expression of the complex. Despite the multiplicity of functions, which included classrooms, workshops, student dormitories, and recreation, the idea of placing all functions into one monolithic structure became essential.

The design took the form of a “Playhouse”, inducing an altogether internalised orientation for the building. An expression that combined the theme of the institute with the idea of a playhouse, where students live, work, play and practice all within a single coordinated space. The entire building was a stage-set, with multiple levels, its central space an amphitheatre; the upper tiers were fragmented, allowing student residents to emerge and define the edges.

Multilevel Crosswalk Garden, Delhi

One of the most critical values that architecture injects into the city is to make madness visible, and take extreme positions—positions that may require, for instance, the insertion of a public library in a metro station, making an art gallery in a slum tenement, or inserting a school within a nuclear power station.

By placing precise moments of culture, recreation or landscape in contradictory situations associated with daily routine, the radical position begins to assert its own humane qualities into urban life; only when insanity becomes an essential ingredient can there be a future of new possibilities. The multilevel garden was proposed over one of Delhi’s busiest traffic roads in the commercial district near Connaught Place. The importance of inserting a raised green space in the most polluted part of town was intended to draw a contrast of functions and raise awareness of the need for green areas where least expected.

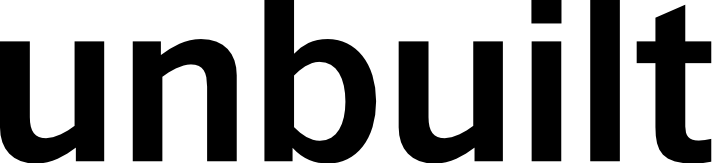

Small House Project

If you drive into the remote hills of Himachal and Uttarakhand in North India, or even beyond any of the big cities to suburban farmhouse territory, across forests freshly cut, on high ridges, you will see, not one, but multiples of ten, twenty, even thirty bungalows—spreading cheek by jowl, on high ground.

Each four bedrooms, with attached baths, living, dining, separate servant’s quarters, garage and service space, what builders describe as 4BHK – a replication of city life in the mountains. Each was built on the principle of bigness and displaying an attitude of utter contempt for efficiency, utility and the surrounding ecology. Big, brash, unmanageable and outmoded may not be mentioned on the brochure to procure their sale, but their presence on once wooded and agricultural mountain land only magnifies the desolation.

Do such places have a future in a country that has for so long neglected its ecology, architectural traditions and available technology? What does the Indian house say about the places we make for ourselves, the poverty of spirit and the call to social and civic disorder?

To fill the gap, the architect has long felt the need to create an imaginary perspective of architectural ideals – driving domestic ideas out of the necessity of mere functional performance into the magnified imaginary logic of oblique and untested ideas.

Could an earth house, embedded deep below ground, provide a collective of insulated rooms around a sunken courtyard? Could a single room make living, eating, and sleeping possible within a compressed space where functions are released and retracted into the wall—a multi-level five-meter cube that could accommodate a whole family, much like a Japanese apartment? Could the home expand, like an accordion, with the growth of the family, enlarging and contracting as required? Could, in fact, a globe house, suspended in the atmosphere, do away with the need for land? The possibilities of building are endless. Architectural space can form below the ground, on the ground, above the earth, or even in the unexplored stratosphere.

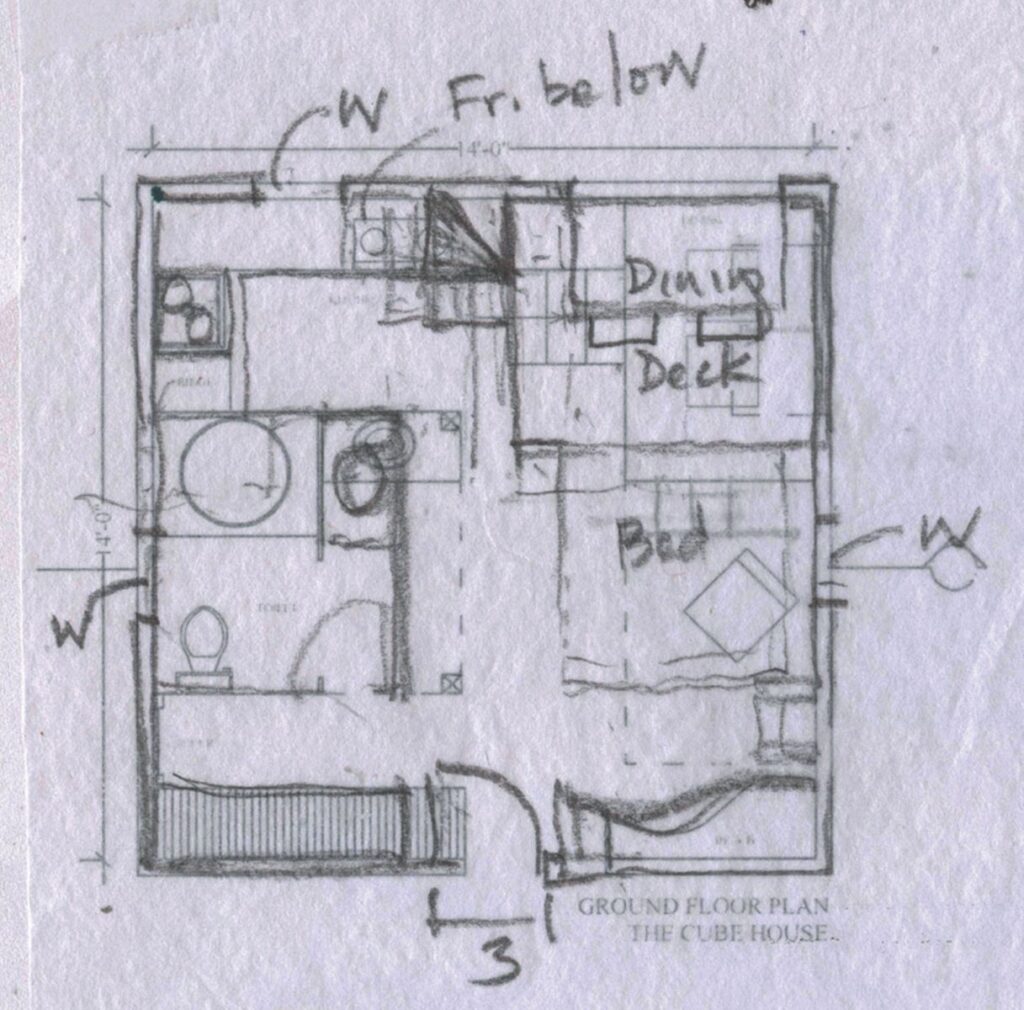

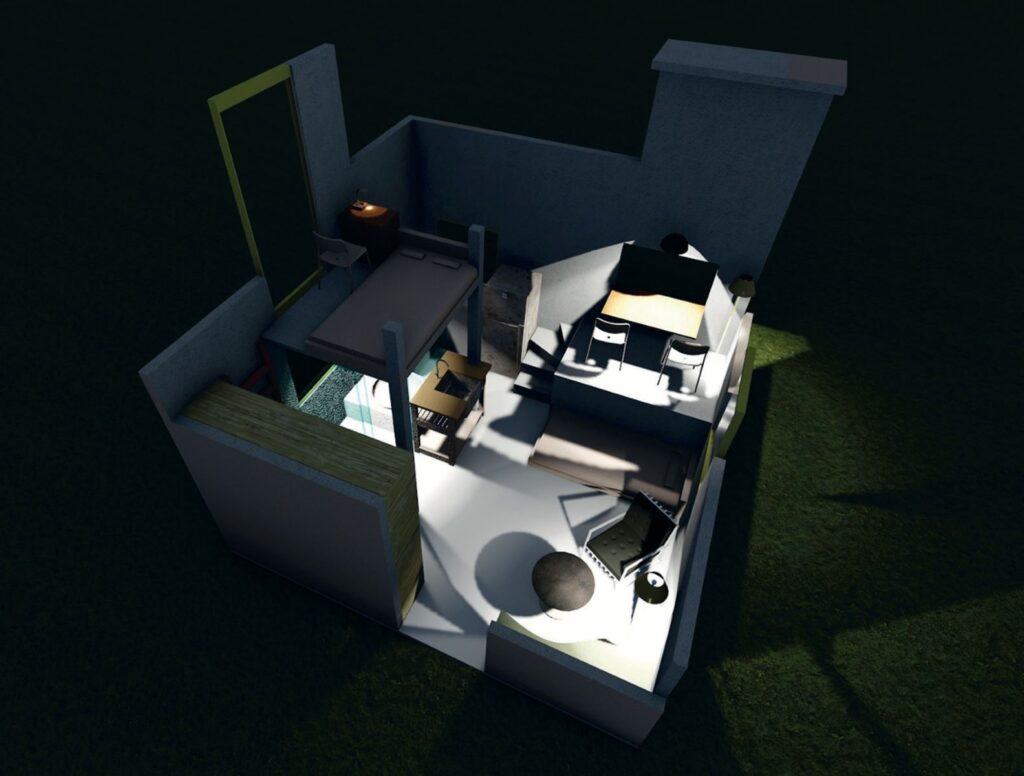

Cube House

The Cube has always been at the heart of all architectural design. Its evolution into a room that becomes a complete home is the outcome of both technology and miniaturisation. Living, sleeping, and eating in a single space that offers instruments of such activity recessed into a wall or sculpted out of it, the Cube House elevates the bed above the bath, and the dining table, when not in use, conceals the window. All actions are formulated in a dynamically shifting space.

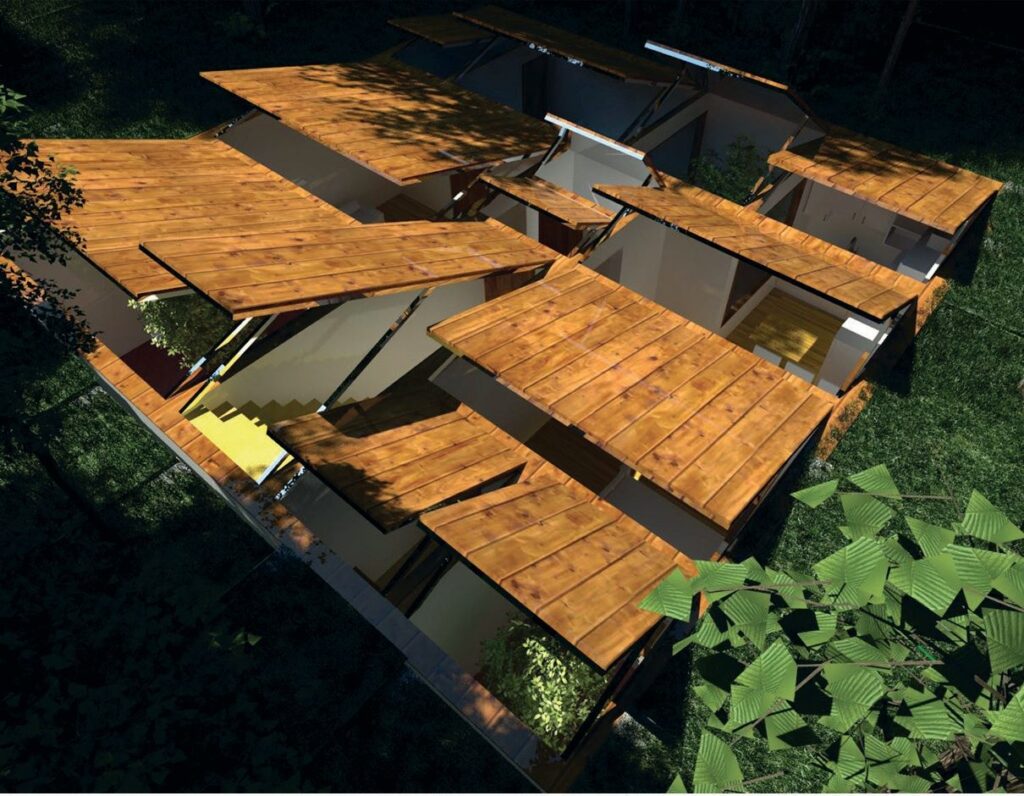

Day Night House

The house is an insert in the forest floor, its roof a wooden platform on the ground. Designed as a day-night house, the home is a complete entity submerged in the earth. Two bedrooms, living and dining with links to underground courtyards and a garden. Relationships of structure, space and size are formed by family needs.

The house position below ground assures, first, a thermal advantage, and second, a design value that erases the dimension and elevation of the enclosing volume. The roof functions as an aperture, a window to the world outside. During the day, the platform lifts as eyelids and allows the sunlight and air to invade the interior, thus connecting each room individually to the forest and sky—an ant’s view of surrounding ecology and atmosphere. At night, the eyelids close and the house sleeps, snug and entirely oblivious to the forest dark above.

Globe House

While the small house reduces the building footprint to a minimum, the Globe House does away with the requirement for land altogether. Suspended in the atmosphere, like an unmoving fish in water, its globular shape occupies minimal surface area. The domestic orb opens at the base to let the residents in, and rises into family space above, achieving a balance between spatial confinement below a complete liberation into the sky above.

Infinity House

Beyond the design of doors that fold into each other and disappear, is there a possibility of rooms that fold and withdraw into each other? A mechanism that allows the house to contract and expand like an accordion, enlarging family space when required. Courtyard to living to dining to kitchen to bedroom and bath, the changing scales and increasing privacy allow rooms to close into each other like a Babushka doll – and fold into a concise package.

Sky House

When the city is a house and the house a city, it opens up numerous possibilities of inhabiting space that no longer confines, but builds up or down, spreads its arms and wings. When a house is not a piece of land but a position in flight, ever in movement. The house is no longer possessed, and is no longer possessed; it belongs in the atmosphere, not in terrain. In the public domain below and soars to private heights, rising from a social life below to personal space above. It produces no skyline, no shape or form or plan, no footprint or air print. Only an atmosphere is made available.