“In many ways, a project remains unbuilt because most of the time it has challenged the normative, the status quo, the acceptability of ‘populist taste’. This is what a reading of history tells us – and why this is important as it inspires future generations of architects to be edgy and provocative.”

— Suprio Bhattacharjee

I have been thinking about the architects that I admire, and their projects that have moved me the most. There have been many over the years, right from the days of architecture school; the list continues to grow as I uncover more gems hidden away in the dense, layered history that is 20th-century architecture. Most of them, if not all, are unbuilt—manifesting themselves in bits and parts in other projects by those very architects, or of those inspired by them.

Oscar Niemeyer’s vision for the Museum of Modern Art in Caracas, Venezuela comes to mind; an inverted pyramid at the edge of a cliff, a sheer triumph of modern materials over relentless gravity – it overcame the need for an angle of repose, unlike the pyramids of yore that owe their stability to the earth’s pull. The inversion of the

pyramid carries with it multiple meanings and connotations – a jab, almost, proud and defiant. This proposal, dating from 1955, has the power to stir one’s imagination and has achieved a quasi-legendary status, easily becoming one of the 20th century’s most beloved unbuilt icons.

Resembling a tree perched at the edge of a precipice, its internal spaces – column-free, spanned across by floor slabs in tension, tying the leaning concrete walls together – would perhaps have been the ultimate achievement by an architect whose works continue to exude remarkable otherworldliness, emphatic optimism, and freedom. Utilizing Architecture as a means to transcend the generic, Oscar Niemeyer’s works often bring to mind the visions of artists such as Jean Giraud and Syd Mead – visionaries who painted future cityscapes for films and comics, propositioned as abstractions of reality that brought to light the challenges of the present, as much wonder as they were warnings. Like the works of Archigram and Superstudio – collectives that were not formed with the explicit intention to build, but rather to instigate and provoke – Niemeyer’s work distilled the anxieties of the 1960s and 1970s into questions of people, place, politics and production.

Mies van der Rohe’s 1921 competition entry for building Berlin city’s first high-rise on Friedrichstrasse is another favourite, an icon of early modernist architecture; the photographs of the model and the drawings are unforgettable – a remarkable early vision for a steel-framed skyscraper wrapped in glass, with three jagged crystalline wings (the early Mies owed a lot to the German Expressionist Architecture movement – another minefield for unbuilt visions) anchored by a central service core. A strangely organic plan that neatly segregated spaces of circulation and occupation, Mies’ work even foresaw Louis Kahn’s famed ideas of ‘served’ and ‘servant’

spaces. Louis Kahn himself would later envision a massive vertical city for Philadelphia in the late 1950s – a staggered latticework megastructure suggesting a dense vision for freeing up the downtown that was being wrecked by unplanned density and the automobile.

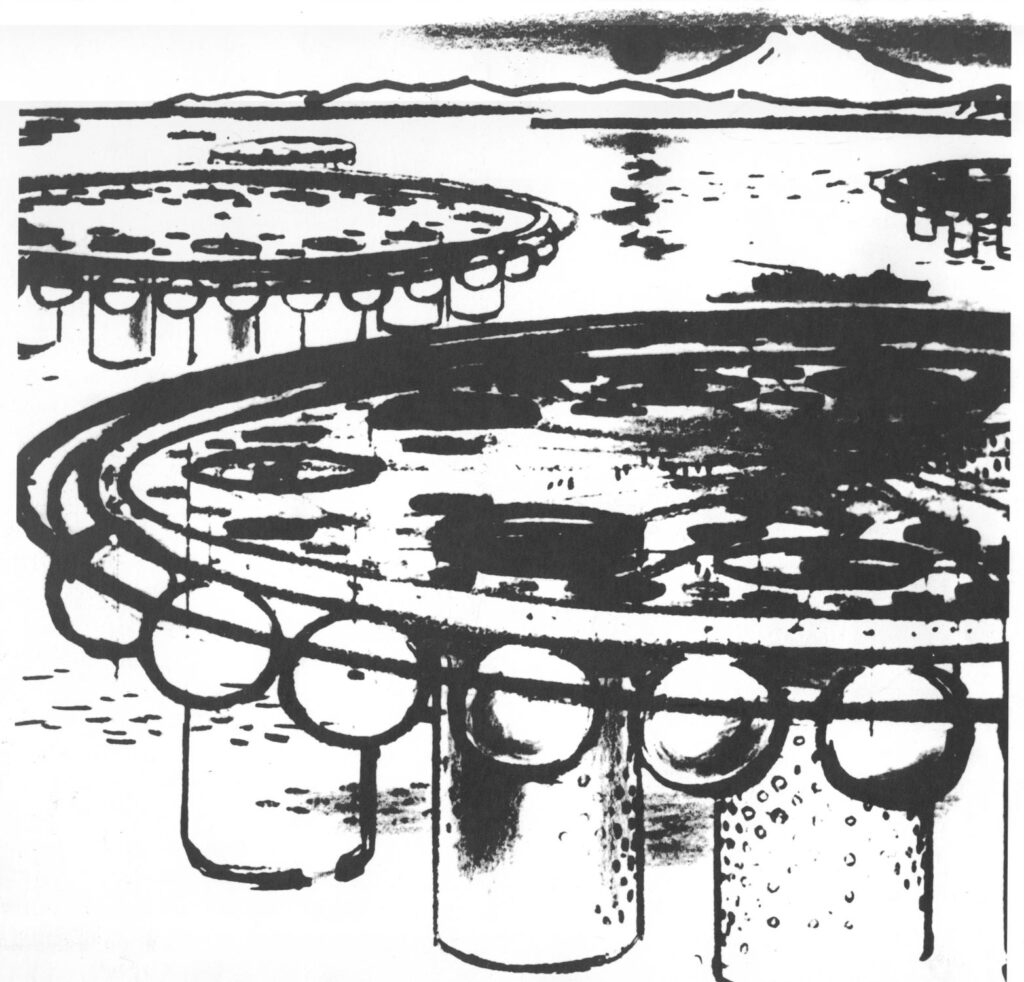

Across the Pacific in Japan, the Metabolists – as they were known – were envisioning ways to deal with Tokyo’s post-war urban explosion in its new guise as a global centre, hoping that a fusion of biomimetic growth with advances in technology would provide answers. While their fantastic urban visions, such as Kiyonori Kikutake’s Marine City or the famed Tokyo Bay Plan (Kenzo Tange with Kisho Kurokawa and Arata Isozaki), never saw the light of day, they did inspire an entire generation of architects and urbanists across the world to think of radical solutions. Consider Norman Foster’s own unbuilt Hammersmith Centre or his Millenium Tower proposals for both London and Tokyo, the latter being a no-holds-barred tribute to Kiyonori Kikutake’s Marine City – besides of course the Metabolists’ own translations of these ideas into the exceptional, unbridled architecture that emerged in Japan during that period distilling ideas of the body and technology into built manifestations.

These had a profound impact upon an entire generation of visual artists – Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon, and Mamoru Oshii, amongst others – who brought this bio-machine aestheticism and the subsequent philosophical conundrums into their own body of work of remarkable anime. It is at this juncture that I propose the idea of the Anti-Practice, much like Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s reading of Umberto Eco’s massive 30,000 book collection as an ‘Anti-Library’ – based on Eco’s own assertion that the books more precious on the shelves are the unread ones, those yet to be discovered and experienced.

This offers remarkable commentary on the idea of ‘gaining’ or ‘acquiring’ knowledge, positing that all acquired knowledge – all the books one may have read – stands meekly against the mountain of books one hasn’t read, and thus cannot or should not be used as a trophy to rise in the pecking order, something that afflicts contemporary Academia – and by that extension, society – enough to strangulate discovery and invention. In a similar vein, I suggest that buildings and urban visions more precious to a culture or to the profession are the ones that haven’t been built, as they leave us with enough that is yet to be experienced, yet to be discovered, yet to be engineered, yet to be critiqued, yet to be lived-in. And what possibilities the Anti-Practice holds!

Many architectural cultures (especially the advanced ones) are built upon a discourse around the unbuilt and the envisioned. Much like science-fiction, which remains fiction until it becomes fact decades later, such as the 1960s Star Trek series’ communicator becoming your cell phone – unbuilt architecture has the power to proposition a future. Who can forget Antonio Sant’Elia, that prodigious talent whose entire body of work is essentially an example of Anti-Practice that heralded new paradigms of modern architecture and urbanism, manifested in drawings from the early 1910s.

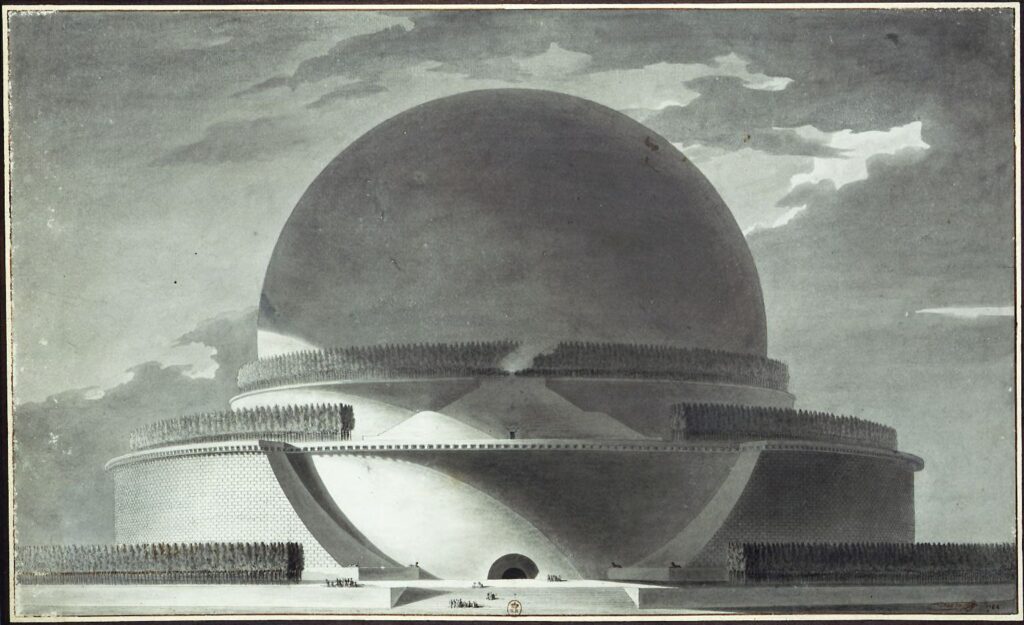

The history of architecture is filled with examples of the Anti-Practice. Etienne-Louis Boullée proposed a daring spherical architectural construct in 1784 to mark Newton’s 150th death anniversary – higher than the pyramids of Giza, the structure symbolised a forceful defiance of the forces of Gravity in honour of the individual who discovered them. In the mid-1800s, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc conceptualised architectural strategies that fused previous traditions with the possibilities that iron construction allowed – Structural Expressionism, as it is sometimes called; his explorations predate the High-Tech architecture tradition of the 1960s. The Industrial Revolution, too, was rich fodder for many unbuilt visions, including Thomas Telford’s Iron Bridge across the Thames in London, dated 1801 – a filigree latticework of metal that exudes a tremendous lightness.

However, it would be incorrect to associate the unbuilt only with a certain technical or financial competence, or a mere assertion of bravura. The Anti-Practice is where architects also strike a political pose.

What can be more profound than envisioning architecture that is a direct result of the turbulent times – especially in cultures where these unbuilt visions are akin to books, cultures that believe in publishing and the print medium, cultures that are based upon the dispersion and sharing of knowledge. The authorities, consequently, were terrified of the radical propositions of the Soviet modernists of the 1920s, the original avant-garde; architects who really stuck their noses out to celebrate individual freedom of expression – the Suprematists and the Constructivists and everyone in-between – championing the embrace of technology and modern ideals of democracy and transparency in a country that was undergoing tremendous social and cultural change fuelled by political propaganda. This polemic power of architecture, amplified by political consonance, has been best embodied by the Anti-Practice.

Ultimately, the most precious projects for the profession as well as the practitioner of architecture, are the Unbuilt ones. These remain unbuilt for a number of reasons; one should not forget that two of the most remarkable buildings that won Millennium Commission competitions (a massive undertaking for public projects funded by the British Government in the late 1990s) were won by foreigners and never built for shockingly frivolous reasons – something that foretold today’s Brexit drama of a supposed ‘British-ness’. One project – the Cardiff Bay Open

House – was won by Iraqi-born Zaha Hadid, and the other – the Bristol Opera House – was won by Gunther Behnisch, a German post-war democratic architecture proponent. The saga of these two projects, widely published and documented in the media, highlights the necessary political struggles of a project—predominant among these is the responsibility of an architectural venture to make administrators and upholders of the status quo uncomfortable, and in turn, re-vitalise a generation of architects.

This discomfort is the seed of transformation and changes the views of cities and societies; in many ways, architectural practice has been paving the way for these shifts in perspective, if not instigating them directly.

The intention, thus, is to demonstrate the importance of having a historical archive for the unbuilt – and by extension, the importance of a book like this. In the absence of discourse, we tend to accept compromised and diluted visions as the standard (like the now-forgotten original New Bombay masterplan); worse still, we tend to forget and undermine visions proposed in a certain past – such as the Bombay City Centre proposed by S.W. Sangamnehri in the 1970s, which could have positively altered the landscape, pre-empting as it did the challenges of the present city. Or Charles Correa’s unbuilt competition-winning scheme for the Museum of Islamic Arts in Doha, Qatar – replaced later by a bland building by I.M. Pei, as the ruler of the land wished for an ‘International Starchitect’ to build his trophy-building; a study in geo-political aspirations, the circumstances threw light on why Jean Nouvel was still needed at the time to build a museum in Doha or Abu Dhabi to make the region appear ‘open’ and ‘diverse’ enough for foreign (read western) investors – although that is no longer really true in today’s post-global scenario.

Another remarkable instance is the unbuilt master plan for rejuvenating the Lodhi Garden by Joseph Allen Stein – a proposal that envisioned a blurring of the edges between garden and city, nature and artifact, to bring the Lodhi Garden into the 20th century. Unfortunately, what we have today is a garden hedged off from the city, and Stein’s brilliant India International Centre forming the edge of a landscape it was meant to be a part of, not disconnected from. These were not necessarily projects before their time, as much as projects of their time – as is the curse of those who are able to see into the future. In many ways, a project remains unbuilt because most of the time it has challenged the normative, the status quo, the acceptability of ‘populist taste’. This is what a reading of history tells us; these records remain all the more pertinent as they inspire future generations of architects to be edgy and provocative.

If nothing else, a study of unbuilt projects can also be just pure unadulterated fun – like knowing that architecture’s original enfant terrible Rem Koolhaas essentially took an unbuilt private house from 1998 and scaled it up for his competition-winning (and eventually built) Casa da Musica proposal sited in the middle of an important roundabout in the Portuguese city of Porto. A boulder-like spaceship that sits squarely in the middle of a UNESCO-designated world heritage precinct, the design is utterly modern and 21st century in its abstraction, yet resoundingly urban and totemic. A silly move, apparently, but serious in its execution – who knew that one could pull out an unbuilt idea for somewhere else onto elsewhere?