Preamble: The Architecture of Absence

What if the most successful architects of the future aren’t the ones who build the most, but the ones who build the least—one where the act of not-building becomes as generative as the act of construction itself…

This absurd and counterintuitive idea sits at the heart of a discussion between renowned architects Gautam Bhatia and Ramu Katakam, moderated by Mrinalini Ghadiok, during the launch of the book “Unbuilt 2.0: Architecture of Future Collective“. Here, in the interstices of this conversation—rich with insights about professional practice, societal transformation, and the role of imagination in shaping our built environment—emerges a contemplation on what it means to dwell architecturally in an age of environmental crisis and social transformation.

The Dialectics of Emptiness and Necessity

To understand the relevance of this conversation, it is important to consider what the COVID-19 pandemic revealed about our built environment: the simultaneous existence of surplus and scarcity within the urban fabric. Office towers that cost crores to construct stood empty for months while governments scrambled to create isolation facilities. Homes designed for rest suddenly had to accommodate work, education, and exercise simultaneously. The contradiction was telling. As Ghadiok noted during this discussion, “Here you have the Delhi government struggling and fighting every day to build isolation camps… was there a possibility to use the existing infrastructure for something like this [isolation camps], which was a requirement of the hour?”

These contradictions prompt a fundamental question: are we building the right things, in the right way, for the right reasons?

The answer reveals architecture’s core problem. We have created a world where buildings serve single, rigid purposes rather than adapting to human needs as they change. Even more troubling, we continue building at a pace that seems disconnected from actual necessity. Bhatia put it bluntly when he described India as one of the “most overbuilt countries on earth”. But he also offers a radical response: “the architectural practices that actually build less are the better practices—less meaning they accommodate; they find innovative ways to adapt existing buildings.”

The metaphor is deliberate—imbuing a surgeon-like ability to intervene minimally yet transformatively within existing spatial conditions. Bhatia envisions architects as spatial surgeons, making precise interventions in existing structures rather than performing wholesale replacements. In his questioning of why “so much of India is destroyed when construction is required, as 30 million people need to be housed,” Bhatia reframes building activity as environmental inscription, where each new structure represents both human shelter and ecological cost.

This shift requires what Katakam identifies as perfect timing. “If we don’t make a change now due to this pandemic, then when are we going to do it?” He argued, “because it [pandemic] has shown us that many possibilities are available to us through technology.”

The pandemic didn’t just disrupt normal patterns of living and working. It revealed the flexibility hidden within spaces we had assumed were fixed in their functions.

Kitchen tables became office desks, bedrooms transformed into classrooms, and suddenly the rigid categories that typically define buildings seemed less important than their capacity to adapt.

Yet both architects express scepticism about whether this revelation will translate into lasting change. Bhatia observes that “we are an adaptive culture, and we would be happy to work on the dining table at home rather than… look at an architectural possibility of coming out of the pandemic.” This adaptability, while admirable in some ways, may prevent us from questioning why our spaces work the way they do. We adjust ourselves to buildings rather than expecting buildings to adjust to us. As Katakam notes, “it’s not the architect who starts the process of change… it is the people in power in what they want.” Architects typically respond to client demands rather than driving transformation themselves.

This creates a cycle where innovative ideas remain trapped in the realm of the unbuilt because construction systems remain conservative. Major architectural changes require what Bhatia calls “serious backing—financial backing as well as political backing.” Without institutional support, even brilliant solutions remain drawings rather than built reality.

Writing as Spatial Practice

Perhaps the most intriguing dimension of this discourse involves the recognition of writing as a legitimate architectural practice.

Bhatia, Katakam, and Ghadiok have found ways to work within these constraints by expanding what they consider architectural practice. Rather than limiting themselves to designing buildings, they have become architectural writers, researchers, and critics.

Katakam’s scholarly work on Kerala temples emerged from “not being able to build the manner we wanted to”. His research becomes architectural archaeology, uncovering spatial wisdom from historical traditions that achieved remarkable consistency and beauty over centuries.

Bhatia’s satirical writing serves a different but equally important function. His documentation of what he calls “ludicrous ideas” from clients reveals the often-absurd motivations that drive architectural projects. By making these dynamics visible through writing, he performs a kind of cultural criticism that helps both the profession and the public understand the forces that shape our built environment.

Ghadiok’s articulation of her own departure from traditional practice—”provoking thought, trying to question the norm, trying to understand what is happening, why it’s happening, and challenging that”—positions criticism itself as an architectural act. Her work suggests that the most important architectural interventions might occur not in space but in consciousness, shifting how we perceive and value the built environment.

The “Unbuilt” as Possibility

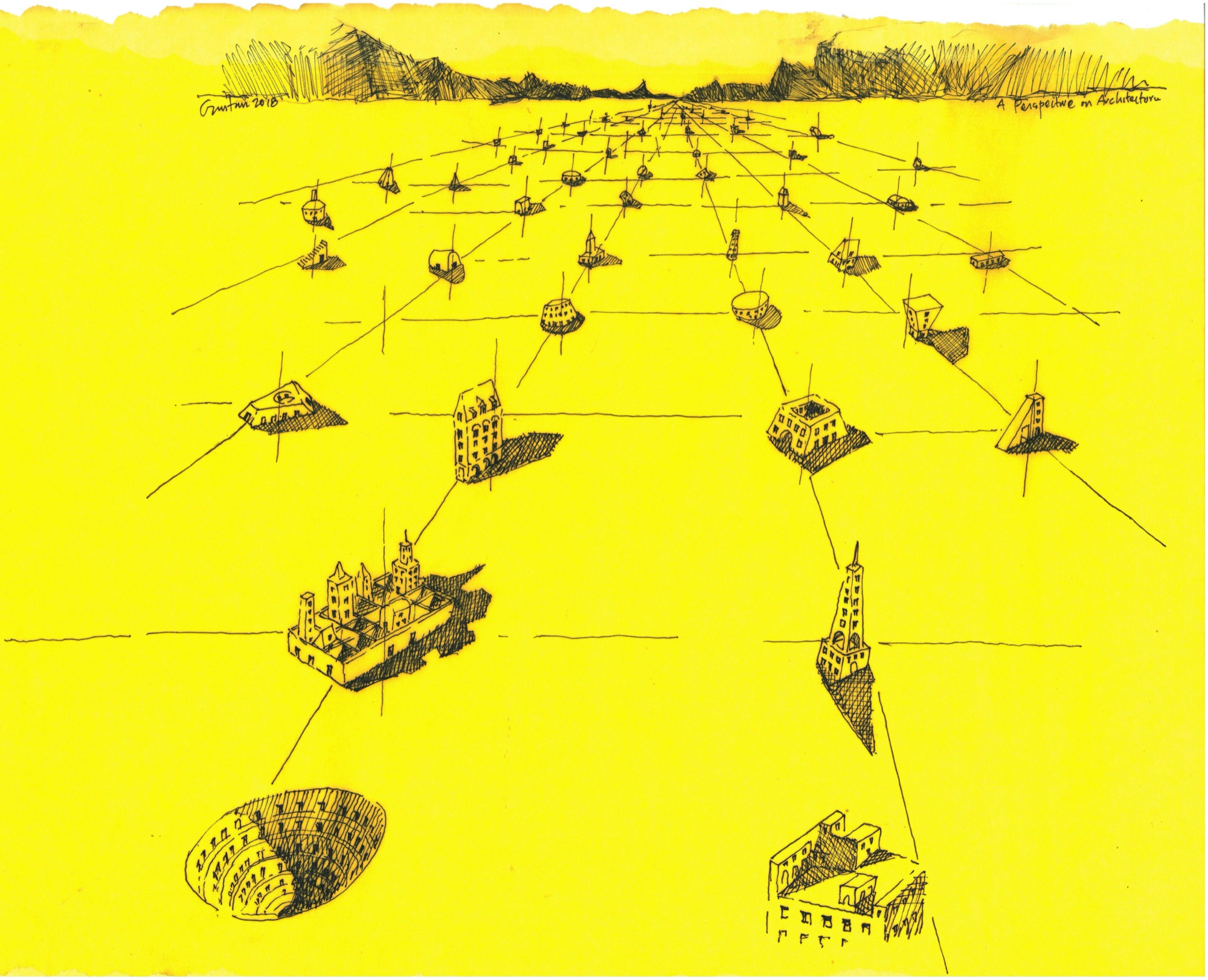

With so much that has already been built and the issues that cropped up, the concept of what “unbuilt” can represent becomes important—unrealized projects which are possibilities waiting to be explored.

As Bhatia explains, “the whole point of looking at the unbuilt is to create a sort of strategy for a very different future.” These unrealized projects function as a repository of possibilities, helping people be more aware of the alternatives to current ways of organizing human habitation.

This understanding transforms architectural drawings from mere construction steps into forms of cultural production. When Bhatia argues that architects need to “draw those things out, we photoshop them, we make people aware that there are other scenarios which we can work with,” he positions visualization itself as architectural practice. These images become arguments for different ways of living—working proposals that exist in the space between imagination and reality.

The social justice dimensions emerge clearly in Bhatia’s challenge about what kind of living poor people in cities deserve. Drawing parallels to Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” program, he argues that unless architects address “such esoteric topics” as beauty and lifestyle for all economic levels, architecture risks being reduced to mere problem-solving rather than creating meaningful human environments.

This thinking requires productive rule-breaking. Bhatia points to New York’s variance committees, which allow builders to add floors in exchange for creating public plazas—strategic departures from regulations that benefit everyone. Innovation often requires questioning why rules exist and whether different approaches might serve collective interests better.

Critical Tensions

Furthermore, the conversation reveals three fundamental tensions defining architecture’s current moment.

First, there is the choice between adapting existing buildings versus constructing new structures.

Second, there is a tension between innovation and tradition, between exploring radical possibilities and learning from successful historical approaches.

Third, there is a gap between individual architectural vision and systemic change.

Bhatia believes younger practitioners offer hope, having “much broader views of building” and being more open to transient or digital forms. He suggests they might become “enablers and collectors or they need to become botanists and surgeons,” specializing in the “surgery of the city” through careful intervention rather than wholesale construction.

Yet the conversation acknowledges the risk of architectural nostalgia, where architects retreat into producing “beautiful buildings for themselves” rather than engaging with contemporary urban realities. This retreat into familiar territory may prevent the profession from engaging with radical possibilities the current moment demands.

The urgency becomes clear when considering global challenges. Climate change demands dramatic reductions in resource consumption. Urban inequality requires spatial solutions serving everyone rather than privileging wealthy populations. Technological change enables new forms of communication that could reshape relationships between living and working spaces.

The pandemic created what these architects recognize as a rare moment of possibility, when established patterns were disrupted enough to make alternatives visible. But such moments don’t last forever. The question becomes whether architecture can change quickly and radically enough to address current challenges.

Architects as Thinkers and Provocateurs

Ultimately, the concept of the unbuilt transcends architectural failure. These unrealized projects constitute a library of possibilities available for activation when circumstances align. They suggest architecture’s most important contribution might not be providing new shelter but expanding collective imagination about how human habitation could work differently.

In a world where environmental crisis demands material restraint, where social inequality requires spatial justice, and where technological transformation enables new forms of dwelling, architecture stands at a crossroads. The conversation suggests that navigating this moment requires not just technical innovation but fundamental reimagining of what architectural practice can become.

The most radical architectural act might be developing the wisdom to know when not to build at all, combined with creativity to find better solutions through careful adaptation of what already exists.

This demands humility about architecture’s environmental impact, sensitivity to social equity concerns, and imagination about possibilities invisible within current thinking about buildings and cities.

Whether this vision becomes reality depends on factors beyond individual creativity—political will, financial innovation, and cultural change that recognizes spatial quality as a collective rather than a private good. But the conversation itself represents an important step, expanding understanding of what architecture might become when it moves beyond building toward comprehensive engagement with how humans inhabit their world.

The unbuilt emerges not as absence but as presence, not as failure but as possibility, not as limitation but as invitation to imagine and create the spatial conditions necessary for a more just and sustainable future. The question that remains is whether we have the courage and creativity to accept that invitation.

Click here to watch the video.