“Buildings stand for much more than the immediate intent of the project, often entangled in the simple equation of articulating and solving a problem. A project, most importantly, represents an ideological position. As we discuss the significance of the body of work in this book, it is important to view an architectural practice as a cultural practice. The work thus produced by any office contributes to the culture of shaping the built environment.”

— Ruturaj Parikh

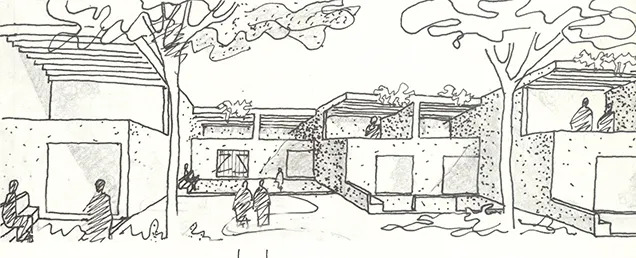

Why do certain projects remain unbuilt? In 2016, while working on an exhibition for Charles Correa’s unbuilt work, we realised that almost one in three projects were never built. These unbuilt projects touched upon many critical aspects and concerns of Charles Correa’s work – from a proposal for reconciliation at conflict-ravaged Ayodhya, to an attempt to resolve a ‘Kanchanjunga Section’ in the Boyce Houses; from competition proposals to commissions that did not take off. The exhibition was titled ‘Buildings as Ideas’ – this title, in essence, outlined the significance of unbuilt work in any architectural practice.

Buildings stand for much more than the immediate intent of the project, often entangled in the simple equation of articulating and solving a problem. A project, most importantly, represents an ideological position.

As we discuss the significance of the body of work in this book, it is important to view an architectural practice as a cultural practice. The work thus produced by any office contributes to the culture of shaping the built environment. If one looks back and reviews the portfolios of some of the most significant practices in India in the past sixty years, it becomes apparent that the intellectual content in a practice is more clearly readable in its body of unbuilt work, as it stays unaltered in its core intent: unsullied by the pragmatic forces of construction.

From this book, one is able to make out the many reasons for a project to remain unbuilt and the multiple positions that contemporary practices in India seem to assume.

Firstly, the book documents commissioned projects that did not see the light of day. For any design practice, failed commissions seem to be a rite of passage! The reasons for such projects to remain unrealised are not readily apparent; however, through the evidence of the work presented, one can decipher the strong vantage points from which the individual architects and offices have voiced their strategies. These vantage points are not just statements of concept; they are also fine articulations of the values of a design practice.

The underlying ideas range from environmental concerns to esoteric and conceptual preoccupations; from issues that deal with immediate contexts to ideas that are typological explorations and have larger implications, much beyond the realm of the project at hand. In a way, one can read the project as a representative outcome of this framework of ideas – if one is able to effectively identify this framework, one can employ the same for works in distinct contexts. While the project itself diminishes, the trace of the idea remains. This residual thought is critical for the projects to come.

Second, competition projects. While the track record of contemporary architectural competitions in India has not been promising, professional competitions of the likes of the National War Memorial enable firms of all scales to compete on a presumably levelled ground. Beyond the basic articulation of the project brief, many abstract and evocative ideas take shape; the content generated by public competitions, if made public, can also seed conversations, challenge conventions and enable one to partake in the study of a wonderful diversity of approaches generated from a singular directive.

Making professional competition projects public is thus essential to the larger critical discourse on architecture. Competitions generate aspirational content and often signify the best of the architects’ ability to engage with the programme and the context. They offer an insight into the core concerns of a practice as well as the formal, ethical and philosophical positions of the authors.

Third, self-initiated ideas. While competition projects enable us to look at a multitude of approaches within a comparative framework, self-initiated projects are a glimpse into independent research and design trajectories. This work is critical for understanding the issues, scales and contexts that a design practice is consistently occupied with. Often, these projects remain in various stages of resolution, prompting a conversation on the larger ideas and ideological positions of the authors of such work.

The various fields of operations – from housing to sanitation, from urban design to street realignments, and from pragmatic, clear and site-specific schemes to wishful, utopian and sometimes, unbuildable ideas – all encompass an extremely important collection. It is through these projects that we can decipher the challenges that contemporary architecture practices are willing to confront and the conviction with which they may confront them.

Mostly designed as pro-bono projects with time and finance invested by the studios, the genesis of some such projects lies in the urge to extend known boundaries of contemporary practice, while some projects deal with realms of work where there is a known design deficit. In all, they symbolise an optimistic view of the future where young design offices may wish to tread.

If architecture is cultural production, the urge to nurture ideas without a commitment to translating them into tangible built works is an important endeavour – an inward journey! The common thread that connects all the works published in this book is the overarching audacity with which designers frame the ambition of the project.

Contemporary architecture in India is passing through a confusing epoch. In the absence of a ‘national project’ – and with most work moving into private and ‘exclusive’ realms – one has to look for the ‘content’ in practice: a search for meaning and relevance.

Unfortunately, even the discourse on architecture has moved into the domain of indulgent work with the word ‘lifestyle’ articulating all that money may buy and designers may sell. While one may argue that many practices thrive on this conversation, it is also visible that the more we disengage with larger and more pressing issues in favour of private commissions, the more irrelevant our fraternity becomes to the public at large in a landscape as diverse and with as many urgent challenges as India. What difference, then, will the colour of an accent wall make in a rich man’s second home?

This book points in a different direction. By selection, the majority of projects published here speak about housing, urban design, civic buildings and democratic spaces. The questions raised by these projects are relevant now and will continue to confront our profession in the years to come.

This book is also an optimistic endeavour – an attempt to search for value in abstraction: an attempt to look for traces of thought in piles of visual material. While the projects published in this chronicle will never be realised in their complete

and intended form, they form a datum – a fertile ground for the ideas to come.