Most good literature, and cinema by extension, opens up worlds of “what ifs?” for readers and moviegoers. The unrealised tangents of a story, when strong enough to draw attention, tantalise the audience into contemplating alternative possibilities. Especially since the Internet became the dominant avenue for accessing books and films, any project teased to the public becomes the focus of often feverish speculation. Arguably, such an excitable fan base existed earlier: Federico Fellini’s 1963 film 8½ (Otto e Mezzo) is an example of a genre that testifies to the impact fans have on moviemakers, musicians, and other creators.

Many creative folks start as fans of earlier artists, whether or not they are insiders privy to industry news, and their response to unrealised films bears examination. Here, a line must be drawn between unfinished or unbuilt films, which were abandoned despite being written and/or shot, if only partly, for reasons discussed hereafter, and unreleased or lost films that were completed but never brought out on screens large or small. Some unfinished films may be half-built: some footage is available for public viewing, possibly thanks to rescue efforts. Lost films received some viewership, among those in the know, who may have drawn inspiration for their own subsequent creations.

Fortune (may not) favour the brave (writer)

Screenwriter and film critic David Hughes, setting the context for his Tales from Development Hell 1, refers to the producer and author Jane Hamsher to explain “in theory” Hollywood’s film development process:

“The writer turns in a script. The producers and studio executives read it, give the writer their ‘development’ notes, and he goes back and rewrites as best he can, trying to make everyone happy. If it comes back and it’s great, the studio and the producers will try and attach a director and stars (if they haven’t already), and hopefully the picture will get made.”2

Notwithstanding Hughes’s disclaimer of “naturally favour[ing] the writer”, his thesis points to the lack of consensus regarding the script’s (commercial) viability as one reason for films remaining unbuilt. One example is a 1988 Planet of the Apes (Franklin J. Schaffner, 1968) remake pitched by then Hollywood newbie Adam Rifkin to Craig Baumgartner, head of 20th Century Fox at that time, which failed to materialise once Baumgartner was “unexpectedly and unceremoniously replaced”. Rifkin, who later described this “first studio job” 3 as “a valuable personal and professional experience”, looked back on the debacle as:

“There was no grand deceitful moment or imposing closed-door meeting that put the final nail in its coffin. Trends shift, culture changes, new ideas replace old ones, and what once seemed like a great idea to a studio and its marketing department now seemed like old news.”

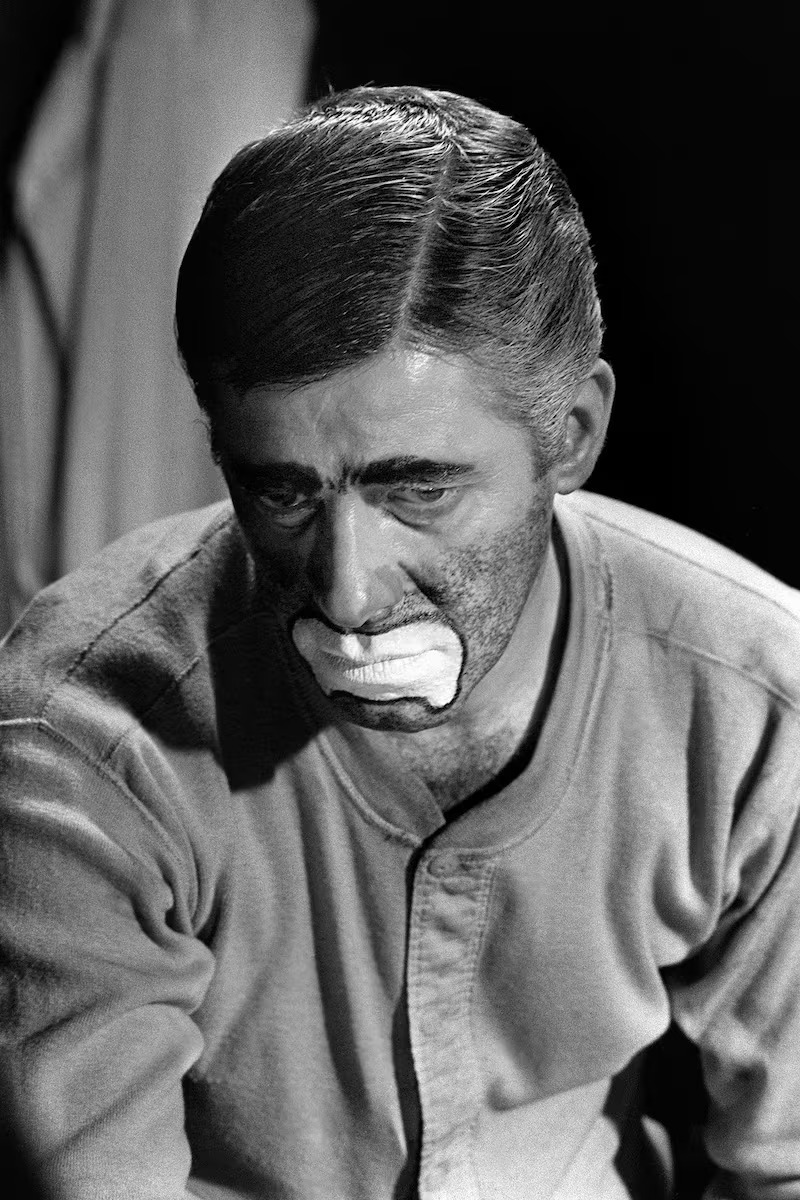

Unlike Rifkin, the Indian filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak was not a newcomer to the Calcutta or Bombay film industries in his time. A Marxist filmmaker and member (for a while) of the Communist Party of India (CPI), Ghatak saw films as a “weapon in the struggle against structural discrimination and systemic injustice” 4. His career comprises unbuilt, half-built, and probably lost films, starting with his 1948 collectivised attempt at guerrilla filmmaking (Jomir Lorai/ The Struggle for Land), which remained unbuilt for political reasons—Ghatak and his Communist collaborators were considered subversive in a newly independent India.

A decade later, after his falling-out with the CPI, Ghatak teamed up with his fellow Bangla filmmaker Bimal Roy to write and co-script Bombay’s most successful film of 1958, Madhumati. In the two years prior, he had worked on “a number of scripts”5, none of which ever became a film. While one of these scripts, Notun Phashal (The New Harvest), initially caught the producer B.N. Sircar’s attention—giving Ghatak the hope of pursuing his experimental cinema again—by mid-1957, “Sircar abruptly withdrew from the project, citing financial uncertainty and indefinite delay in starting the work” 6.

Ghatak lamented that Indian film-making’s “financial roots are unsteady” 7, and blamed exhibitors:

“But the exhibitors never gamble. They just make a cinema hall, and they are not only guaranteed the value of their investments but they are guaranteed even a huge amount of profit… It is also worth noting that there is no credit system in the show business. All the exhibitors’ earnings are in spot cash. And they never, or very rarely, re-invest money into the film business.”

Over the rest of his career, Ghatak directed and released seven films in two bursts between 1958 and 1963 and 1972-74, almost all of which suffered at the hands of his political and cinematic associates.8 In today’s digitally connected world, would the eager-to-experiment Ghatak have found more willing backers at, for instance, the National Film Development Corporation’s Film Bazaar, which helped “indie” filmmakers like Chaitanya Tamhane (Court, The Disciple) and Raam Reddy (Thithi, Jugnuma – The Fable) find foreign exhibitors and producers? Alternatively, would he have sought to release his films “direct to OTT”, considering that films are now recouping costs more through selling digital (and satellite) rights than through the traditional box office?

Cinema Lost, if not entirely Unbuilt

With Ghatak’s completed works and writings posthumously acclaimed, his repertoire of unbuilt and lost films and scripts also gets due attention. Arupkatha (Not A Myth, 1951-52) 9, for instance (which started life as Bedeni or The Snake-charmer Woman, before Ghatak was brought in), would have earned him his first directorial credit. It was, however, abandoned after 20 days of shooting due to “a fault in the camera”. Ghatak’s first completed film, Nagarik (The Citizen), although cleared for release in 1954, did not reach theatres until 1977—well after Ghatak’s passing. Put together, his career offers a nuanced caveat emptor for anyone mirroring socio-politico-economic realities in their films.

Source: Cinema and I (Ritwik Ghatak, Ritwik Memorial Trust, 1987)

Further, as demonstrated by the life of the Iranian filmmaker Kobra Amin Saidi (aka Shahrzad), “the ‘unfinished’ can be formed and informed by gender and class” 10. Originally a dancer and singer, Shahrzad achieved stardom as an actress in Iranian films of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Tired of playing stereotypical roles, she turned to writing and then to filmmaking, with Maryam and Mani (1979), “a serious commentary on the economic injustice and poverty that both contributed to the 1979 [Iranian] Revolution and shaped Shahrzad’s whole career” 11. The film was in post-production when the Islamic Republic was established, and consequently, it was never released.

Shahrzad was arrested in March 1979 for filming a protest against the new regime for making wearing the hijab mandatory for women. She was declared a “corrupt dancer and prostitute”, and her work was banned. Later in life, homeless and impoverished, she was forced to sell her films and writings. In the words of her interviewer (in 2018), Tara Najd Ahmadi, “it was Shahrzad’s poverty that made her indifferent toward the set of values and morals that society forced upon women who aspired to be dancers and actresses”, and “motivated her to experiment with other creative opportunities in writing and filmmaking.”

A contemporary parallel from India that underscores Najd Ahmadi’s point is the Hindi film Kissa Kursi Ka by Amrit Nahata. Originally made in 1975, this satire on the policies of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and her influential son Sanjay Gandhi was still awaiting clearance by the Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC) when the government declared a state of emergency. The film’s prints were confiscated from the CBFC and destroyed, for which Sanjay Gandhi was later sentenced to a month’s imprisonment. Nahata, an educator, translator, and crucially, Member of Parliament, remade and released the film in 1978.

Recently, the writer-director Anurag Kashyap dubbed himself “the ‘Most Unreleased Filmmaker’ in India”, having made as many as five films that are not yet released in theatres in India. Given his optimism that at least some of these films may soon see the light of day, it is too early to classify them as lost. Coincidentally, one of the films that hugely inspired Kashyap, Om Dar B Dar (Kamal Swaroop, 1988), achieved cult hit status long before the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) of India released a digitally restored version in 2014.

How the Internet Remembers Unbuilt and Lost Cinema

The Internet is today rife with listicles of “lost”, “forgotten”, or “unfinished” films, with most such pages prone to poor fact-checking and assuming that any project older than one generation must invariably be beyond memory’s grasp. Reliable records of unbuilt cinema (although largely comprising films from Hollywood and other “western” industries) include the Wiki and IMDB lists of unfinished films, also categorised by artist. The IMDB list, with its at-a-glance summaries, grimly chronicles how death affects a film’s completion. One example is the 1963 Polish film Pasażerka (The Passenger), assembled and released unfinished after a car accident ended the life of its director, Andrzej Munk.

One of the oddities in Internet-based cataloguing of films is exemplified by the Werner Herzog-directed German short film, Spiel im Sand (Game in the Sand, 1964). Most of the information available online about the film is sourced to Herzog himself, including the fact that the film was abandoned after “shooting got out of hand”, it was never shown publicly anywhere, and that Herzog “will never release it in his lifetime”. Yet, mysteriously, the film’s IMDB listing includes a rating of 8.1 (out of 10), based on 42 users’ inputs. The usual explanation for such ratings is that people have seen pirated versions, or that the films have been released in some geographies but not others. Neither is the case with Spiel Im Sand; perhaps this information, too, will have/ have to come from Herzog himself.

The internet, as an extension of human memory, also plays into nostalgia.

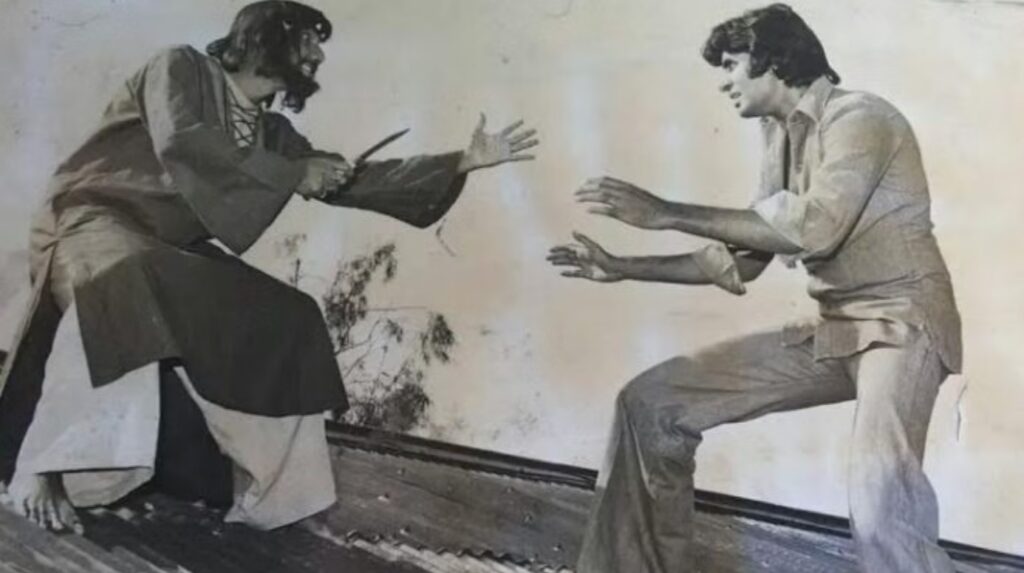

Many Odia and Axomiya (Assamese) film fans, for instance, recall an unfulfilled 1970s project involving Amitabh Bachchan. Before Kushaljeet (Tito) and Ramanjit (Tony) Singh Juneja made their name in the Hindi film industry, Tito was producing Assamese films. Tony followed in his footsteps, starting as a Production Boy. During their early days, which coincided with the beginning of Amitabh Bachchan’s career, they collaborated in an ambitious but ill-fated adaptation of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist.

The trilingual production, on whose timing digital memory is incoherent, only involved about a week of shooting in Kolkata. The Axomiya version was titled Sonti, with Mukta the Odia title. All that remains of the project are reminiscences by the actor Dinesh Das (cast as the Fagin-equivalent character, Fatik Chand, in Sonti), who noted that Sombhu Mitra would have played his character in the Bangla version, a couple of photographs, and the speculation whether these films would have been completed had it not been for the success of Zanjeer (Prakash Mehra, 1973).

Reviving Lost Cinema – and (re)building the Unbuilt

One of the most talked-about unfinished films is The Day the Clown Cried (Jerry Lewis, 1972), whose incomplete copy, comprising five hours of footage, is part of Lewis’s career archive in the United States Library of Congress. Lewis directed and partly financed the Swedish-German film in which he also plays a clown in a World War II German concentration camp. He never completed or released it: while working on it, he apparently found it disturbing and even embarrassing. In reality, production issues and a disagreement with the co-authors rendered the film “unreleasable”. Further, those who did get to watch the footage found it “not funny… not good” or, more bluntly, a “disaster”.

Writing in August 2024 about his experience of watching the Library of Congress’s copy after it became available for viewing, the University of Washington academic Benjamin Charles Germain Lee – himself a descendant of a Holocaust survivor – thought it “fitting” that the film “does not exist in final form” and likened it to “memory itself”, “a collection of discontinuous and jumbled fragments that leave you to piece together what is there and imagine what is not”. He asked, “Could it be that The Day the Clown Cried has been unfairly maligned?”

In May 2025, the world discovered, via Swedish news media and the social media platform X, that a version of Lewis’s film had been illegally duplicated by a Swedish actor, Hans Crispin. Thanks to an anonymous contributor sending Crispin footage missing from the bootlegged copy, the latter was able to create a complete version of the film and exhibit it to journalists to authenticate his claim. Crispin has since sold the copy, leaving the film’s ultimate fate still uncertain. But the digital following of the film is only likely to grow, especially with a remake becoming possible, thanks to K. Jam Media founder Kia Jam acquiring the rights to the original script by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton.

A stark contrast to Lewis’s fictional account of the horrors of a concentration camp is another lost film, Theresienstadt, a propaganda “documentary” engineered in 1944 by the Nazi Reich’s Schutzstaffel (SS). The film was intended to convince visiting officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) that Danish Jews were living comfortably in the eponymous concentration camp (shown as a “beautified” ghetto). The film, presented as having been made by some of the Jewish people living in Theresienstadt, whitewashed the fact that most of the estimated 140,000 inmates either died there or were deported to extermination camps. Most of the film’s footage was lost by the end of World War II, and while surviving footage is used as research material, no restoration is likely.

The question, however, is whether unbuilt films should be restored, especially with the intent of completing them.

As Lee noted with The Day The Clown Cried, perhaps learning to appreciate the unfinished brings its own reward—of imagining all possible “what if” scenarios. Again, picking up the original script or available footage does not guarantee continuation of the artistic vision that drove the original project, even if some or all of the original personnel involved are available. Tangentially, filmmaker Sandip Ray took on the mantle of continuing the Goopi Bagha franchise begun by his father, the legendary Satyajit Ray, for the third film, Goopi Bagha Phire Elo, in 1992. But he was “extremely wary” of making a fourth film after the passing of the lead actors Tapen Chattopadhyay and Rabi Ghosh, who had played the titular characters in the first three films.

The production company Eros International recently embarked on a supposedly innovative exploration of a “what if” by releasing an artificial intelligence (AI)-edited Tamil version of the previously completed film Raanjhanaa (Aanand L. Rai, 2013). Ram Gopal Varma, who made many highly acclaimed Hindi and Telugu films in the 1990s, shared a video created as a tribute to former danseuse and actress Silk Smitha, featuring imagined portrayals of the actress generated completely using AI. It is not a far cry from such developments to an ambitious producer or director wanting to rebuild or restore an unfinished or lost film. Whether driven by popular demand or in a bid to circumvent financial, production, or distribution pressures, the honesty of such endeavours will always remain suspect.

To return to Adam Rifkin, Craig Baumgartner had not expected him to pitch the Planet of the Apes remake. However, Rifkin set a ball rolling that eventually culminated in the 2001 remake helmed by Tim Burton.

Recognising the beauty of an unfinished film, in this light, is about realising the possibilities it can engender, whether in telling an entirely new story or (re)telling an old story in a new way.

Equally, as the travails of Jerry Lewis’s venture suggest, unfinished films offer insights into the irreplicable creative visions of their makers. While these unmet dreams may divide opinions, their existence, however incomplete, deserves the respect and scrutiny of time, as does any artistic endeavour.

- Hughes, David Tales from Development Hell (New Updated Edition): The Greatest Movies Never Made?, Titan Books, 2012 ↩︎

- Hughes, pg 9, quoting Hamsher, Jane Killer Instinct: How Two Young Producers Took on Hollywood and Made the Most Controversial Film of the Decade, Broadway Books, 1997 ↩︎

- Hughes, pg. 37, quoting Argent, Daniel Evolution, Creative Screenwriting, July/August 2001 ↩︎

- Sen, S. Ghatak in the Shadows: Films that Struggled, Shadow Cinema: The Historical and Production Context of Unmade Films, Bloomsbury, 2020 ↩︎

- Sen, S. Ghatak in the Shadows: Films that Struggled, Shadow Cinema: The Historical and Production Context of Unmade Films, Bloomsbury, 2020 ↩︎

- Sen, pg. 119 quoting Ghatak, Surama Ritwik: From Padma to Titas, Anushtup, 1995 ↩︎

- Ghatak, Ritwik. What Ails Indian Film-Making, Cinema and I, 2nd edn, Dhyanbindu & Ritwik Memorial Trust, 2015 ↩︎

- Sen. pg. 119-120. ↩︎

- Sen. pg. 114 ↩︎

- Ahmadi, Tara Najd Archive of Incomplete, Forty Years of Gender and Sexual Politics in Iran: Marking the 40th Anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, special issue, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, 2020 ↩︎

- ibid ↩︎