Preamble: Beyond the Materialised

Between conception and construction, vision and compromise, exists an architectural territory that challenges the very foundations of disciplinary practice—the unbuilt. For decades, architects have viewed these unbuilt projects with a mixture of disappointment and resignation. They represented missed opportunities, creative visions that couldn’t overcome practical obstacles like budgets, politics, or market demands.

“Unbuilt 2.0: architecture of future collectives” emerges not merely as a publication, but as a philosophical manifesto—a deliberate intervention into the landscape of contemporary architecture. This is one of the few insights that centre the conversation moderated by architect Maanasi Hattangadi, with the three curators of the book, who are renowned architects and theorists themselves—Rupali Gupte, Bijoy Ramachandran, and Ruturaj Parikh.

Their conversation and, to that extent, this article, is a dialogue that reveals not only the content of the book, but also the deeper philosophical questions that drove its creation. It is an access to their thinking process, to understanding how the curators wrestled with the questions which framed the book, and an excavation of architectural possibilities that uncover layers extending beyond the conventional binary of built versus unbuilt.

The Problem with How We Build Today

The transformation between the first and second editions of “Unbuilt” reveals architecture’s epistemic shift from documenting constraints to imagining possibilities. Where the first edition catalogued projects that “were left unbuilt due to lack of budgets, funds and other things,” this second iteration ventures into what Rupali Gupte identifies as “world building”—the systematic imagination of the unbuilt that could support different forms of social organisation.

The difference is not merely semantic. It is a reorientation of the purpose of architecture from problem-solving within existing parameters to questioning the parameters themselves. When Gupte states that “architecture produces the structural logics for this world making,” she positions the discipline not as a service provider but as a social infrastructure designer—one who creates the spatial conditions within which collective life unfolds.

This reorientation occurs against the backdrop of what the curators identify as a “cascade of catastrophes”—ecological collapse, economic inequality, and social fragmentation. The unbuilt, in this context, becomes a space of refuge and regeneration; these projects can explore what Parikh calls “visionary” rather than merely “unrealised” possibilities.

They ask not “How can we build within existing constraints?” but “What constraints should we accept, and which should we transform?”

Architecture of Future Collectives: The Spatial Politics of Association

Central to this reimagining of the book’s subtitle is the concept of “Future Collectives”—a term that operates simultaneously as an analytical framework and design provocation. Gupte’s articulation reveals a sophisticated understanding of contemporary social transformation: the recognition that three decades of intensifying individualism have produced architecture or spatial arrangements that have oriented around property, privacy, and resource exclusivity.

But emerging forms of association—co-working arrangements, co-living experiments, informal institutions, digital communities—suggest different spatial requirements. These “future collectives” are not nostalgic returns to modernist universalism, which “wiped out difference” in pursuit of a homogeneous public space. Instead, they represent what we might call fluid architectures of belonging—spatial systems that accommodate difference while enabling resource sharing and mutual support.

If architecture produces the structural logics for collective organisation, then designing for future collectives requires reimagining spatial relationships. This conceptual framework challenges architecture’s traditional client-architect dyad, expanding toward cooperative models that recognise multiple stakeholders and extended networks of accountability. The architectural project becomes less about serving a singular paying entity and more about creating conditions for emergent social formations.

Critical Resistance Against Architectural Complicity

Perhaps most significantly, “Future Collectives” positions itself as “critical resistance against what’s going on” in mainstream architectural practice. Ruturaj Parikh’s observation that post-1990s Indian architecture has operated “completely in the private domain, completely full of vulgar excesses” reveals a discipline largely captured by capital rather than serving social need.

This critique extends beyond aesthetic judgment to encompass fundamental questions of social relevance. The proliferation of “enormous single-family residences” and “self-congratulatory” corporate projects represents what the curators identify as architectural practice’s complicity in reproducing inequality.

When Ramachandran laments the “almost non-existent” progress in architectural practice over two decades, exemplified by national projects that reduce complex political questions to “carpets and curtains,” he talks about architecture’s retreat from engagement with structural challenges.

The book’s inclusion of academic projects alongside professional work signals a deliberate blurring of traditional hierarchies between practice and pedagogy. As Parikh notes, “academics is not practice is also something that at least now we should move away from because that is actually where values get produced.” This boundary dissolution reflects a deeper understanding that “values get produced” within educational contexts, and that the artificial separation between academics and professionals impoverishes both domains.

Methodological Innovations: Criteria for Critical Selection

The curatorial framework deployed in “Future Collectives” reveals sophisticated methodological considerations that extend beyond conventional project evaluation. The selection criteria prioritise:

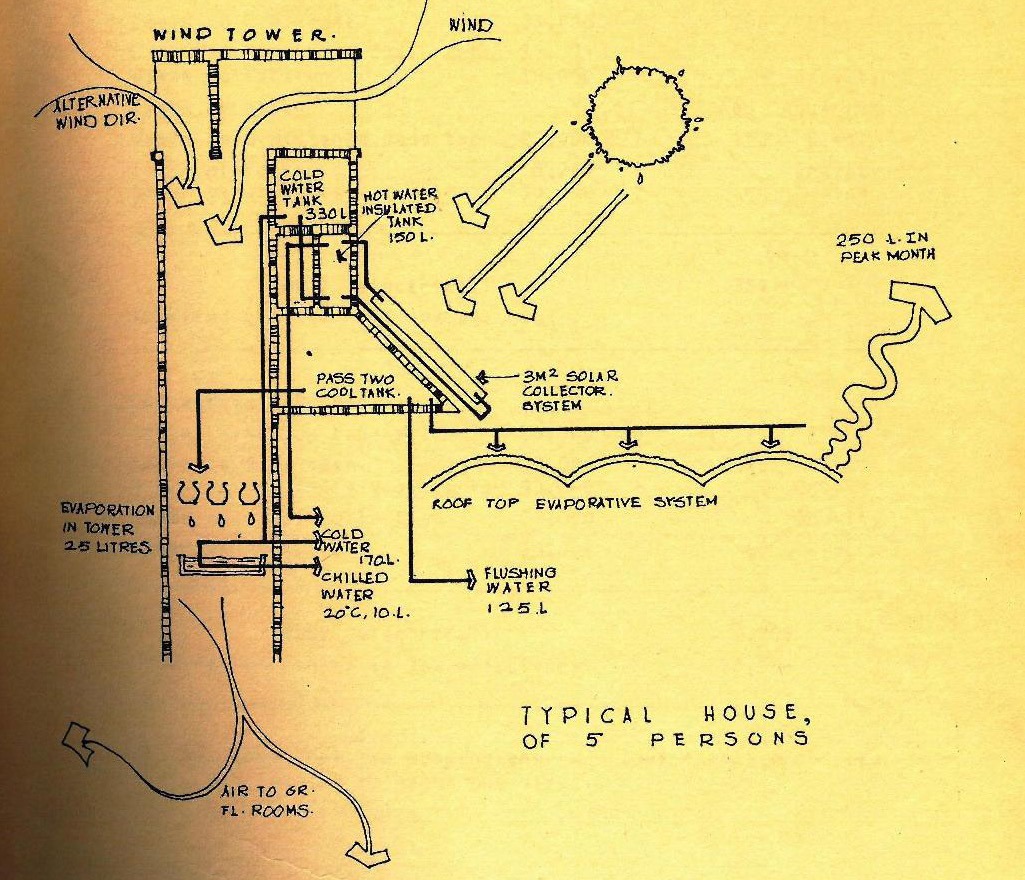

Alternative Representations: Projects that challenge established modes of architectural communication, recognising that “beautiful drawings” can “prompt us to look at the world” through transformed perceptual frameworks.

Spatial Appropriation: Works that engage with “interstitial spaces” and territories “no one is claiming,” demonstrating proactive approaches to urban intervention that bypass conventional property relations.

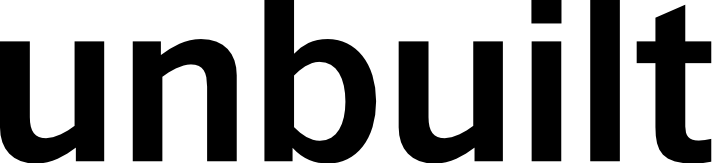

Temporal Flexibility: Projects exploring “ephemeral or temporal” construction methods that challenge architecture’s presumption of permanence, opening possibilities for adaptive, responsive spatial systems.

Expanded Client Models: Initiatives that reconfigure traditional service relationships, incorporating “cooperative clients” and recognising architecture’s potential contribution to commons-based resource management.

Ecological Integration: Works that engage with “repair and restoration,” prioritising intervention within existing urban and natural frameworks over greenfield development.

These criteria collectively constitute what we might understand as a “critical methodology” for architectural evaluation—one that prioritises social relevance, ecological sensitivity, and systemic innovation over formal virtuosity or commercial viability.

The Pedagogy of Provocation

“Future Collectives” operates as an educational intervention, providing what Bijoy Ramachandran describes as “vectors” or “armour against the world” for emerging practitioners. This pedagogical dimension reflects a sophisticated understanding of how disciplinary transformation occurs: not through top-down institutional mandate, but through the cultivation of alternative imaginative frameworks.

The book’s embrace of “messiness” represents a profound challenge to architecture’s persistent fantasy of “Immaculate Conception”—the notion that significant projects emerge fully-formed from individual genius rather than through processes of “negotiation and reflection in action.” This philosophical repositioning validates the iterative, collaborative, and often conflictual processes through which meaningful spatial interventions actually emerge.

Toward Spatial Justice: Architecture as Social Infrastructure

The curators also extend “Future Collectives” toward questions of spatial justice and social infrastructure through projects with the potential to operate as more than aesthetic objects or functional containers—social infrastructure that enables new forms of collective organisation and resource sharing.

BundookSmith Studio’s pavilion explores temporality and ephemerality, questioning architecture’s assumption that buildings should maximise longevity. What if some structures were designed for specific durations, able to transform or disappear as circumstances change?

Biome’s “massive framework” envisions large-scale infrastructure for communal living—not individual buildings but interconnected systems that support multiple ways of organising domestic life while enabling resource sharing.

Pramoda’s reimagining of Prema Bhai Hall demonstrates how existing structures can be transformed to serve contemporary community needs, reflecting broader shifts from new construction toward adaptive reuse and programmatic evolution. Compartment S4’s urban appropriation reveals how overlooked spaces can be activated for community use, suggesting strategies for spatial intervention that don’t require expensive land acquisition or lengthy approval processes.

Projects by artists like Sudipto Ghosh and Riaz use drawing as speculative practice, creating images that help us imagine radically different social arrangements even when precise implementation remains deliberately ambiguous.

Edgar’s cooperative project demonstrates how architecture can serve collective ownership and shared decision-making rather than individual property accumulation.

Many projects focus on what the curators call “ecological sensitivity and repair,” working with damaged landscapes and existing natural systems rather than consuming undeveloped land.

The Unbuilt as Critical Practice

“Future Collectives” ultimately repositions the unbuilt from architectural afterthought to critical practice. The unbuilt emerges not as absence or failure, but as a generative conceptual terrain where alternative spatial logics can be cultivated, tested, and refined before engaging with the actual constructions.

This reconceptualisation carries profound implications for architectural education, practice, and criticism, as the relevance of architectural practice and the profession depends not on the volume of constructed work produced, but on the quality of spatial imagination cultivated and the degree to which that imagination engages with pressing social and ecological challenges.

In the end, the unbuilt emerges not as architecture’s limitation but as its greatest resource of possibilities—the territory where new spatial logics can emerge and where the discipline might recover its capacity for meaningful social intervention. The unbuilt, in this reading, becomes architecture’s most vital territory—the inexhaustible reservoir of spatial imagination from which sustainable ways of living might yet emerge.

The question is no longer whether we can afford such speculation, but whether we can afford not to engage with it.

Watch the conversation here:

Learn more about our curators and essayists here.