In the last twenty years of practice, our firm ABRD Architects has kept busy primarily by competitions – often by winning, but mostly by losing them. Competitions have always fired our imagination – using the opportunity to delve into design charettes. We typically explore divergent options with the intent to question and go beyond the design brief.

Design competitions have played a fascinating role in the history of architecture, with losing entries often being just as important in defining the progress of architectural thought and theory as the actual winning and built projects — the projects that might have been built becoming as influential as those that perhaps should never have been built.

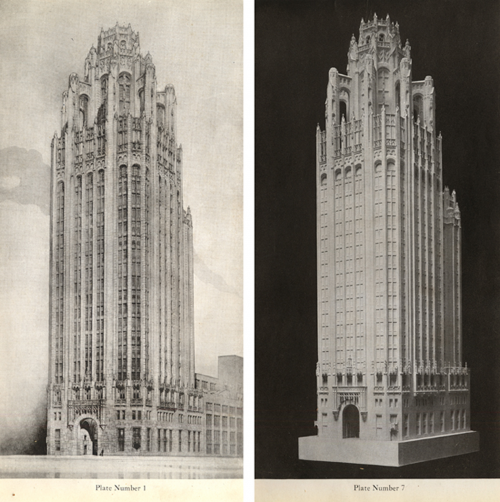

The instances are many: the Chicago Tribune Tower competition of 1922 for “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world” generated tremendous publicity for the American newspaper, and design ideas from some of the 260 entries defining a new direction for modernist architecture and shaping the American skyline for generations to come.

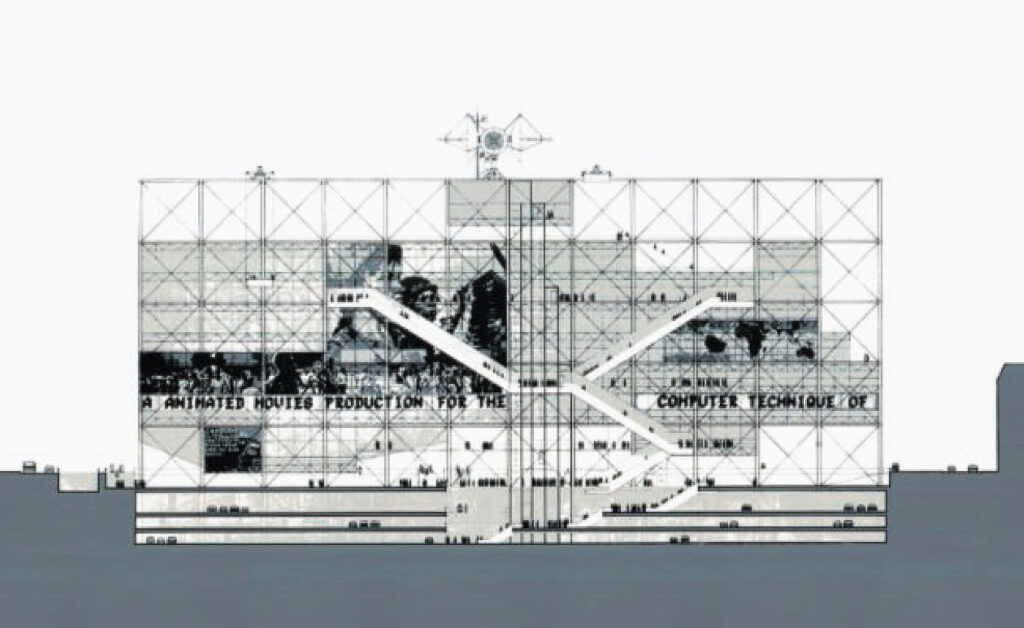

Similarly, in the decades from the 1960s to 80s, France became one of the richest and most active countries in the field of contemporary architecture, and having architects compete with one another in design competitions was instrumental in reviving architectural quality. At the time, France was the only country in Europe with regulations that made competitions a prerequisite for the allocation of publicly-funded construction projects exceeding a certain cost. More than a thousand competitions were organized every year, spanning the smallest municipality to the largest government agency. This quest for design innovation through competition was best epitomized by the Pompidou Centre project, which remains one the most popular landmarks of Paris even after 40 years of its completion. The selection of the then-young partners Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano for the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1971 gave these untested architects the opportunity to establish a new direction with ‘high-tech’ architecture.

Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer’s modernist design proposal for the Chicago Tribune, 1922; made “famous by its martyrdom”, the unbuilt was far more influential than what was ultimately built, a neo-Gothic design by Raymond Hood.

Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers’ winning entry for Centre Pompidou

Recalling their success in the 1976 competition, Peter Rice, the brilliant structural Engineer at Ove Arup & Partners, recalls, “As we sat thinking we realized that a good reason for entering competitions is not to win them but to explore relationships and design. Of course one can hope to win but, particularly when it is an open competition…to set out to win is in a sense self- defeating, because it will induce a conservative and tentative approach and the principal factor will be not to offend.”

“By emphasizing instead a range of unusual ideas which fitted the philosophy and intentions of the architecture, we wanted to fire the imagination… The entry must not become too deliberate or too detailed, or too closely argue a response to the brief, because the jury will only have the briefest time with each entry. It is the idea they will see and the spirit of the drawings.1”

Competitions were less common in Asia, with Japan being the first country to really embrace the method, organizing several well-publicized architecture competitions in the 1980s in an attempt to project an image of a fully recovered nation post WWII. Although there is no documented history of competitions in India, we can assume that architectural competitions appeared in post-independence India during the Nehruvian era. One of the earliest competitions conducted was for the design of Raj Ghat, which was won by architect Vanu G Bhuta. Competitions got a boost with important events like the 25th anniversary of India’s independence in 1972and the Asian Games in 1982. Though some competitions were open, most were limited in nature where established architects were invited to participate, perhaps owing to the limited size of the Indian architectural fraternity in the decades after independence. Open-for-all architecture competitions were organized widely in the last quarter of the 20th century, with prestigious projects like Jawaharlal Nehru University, I.G. Stadium, J.L.N. Stadium and Bhikaji Cama Place district Centre being the results of such endeavors.

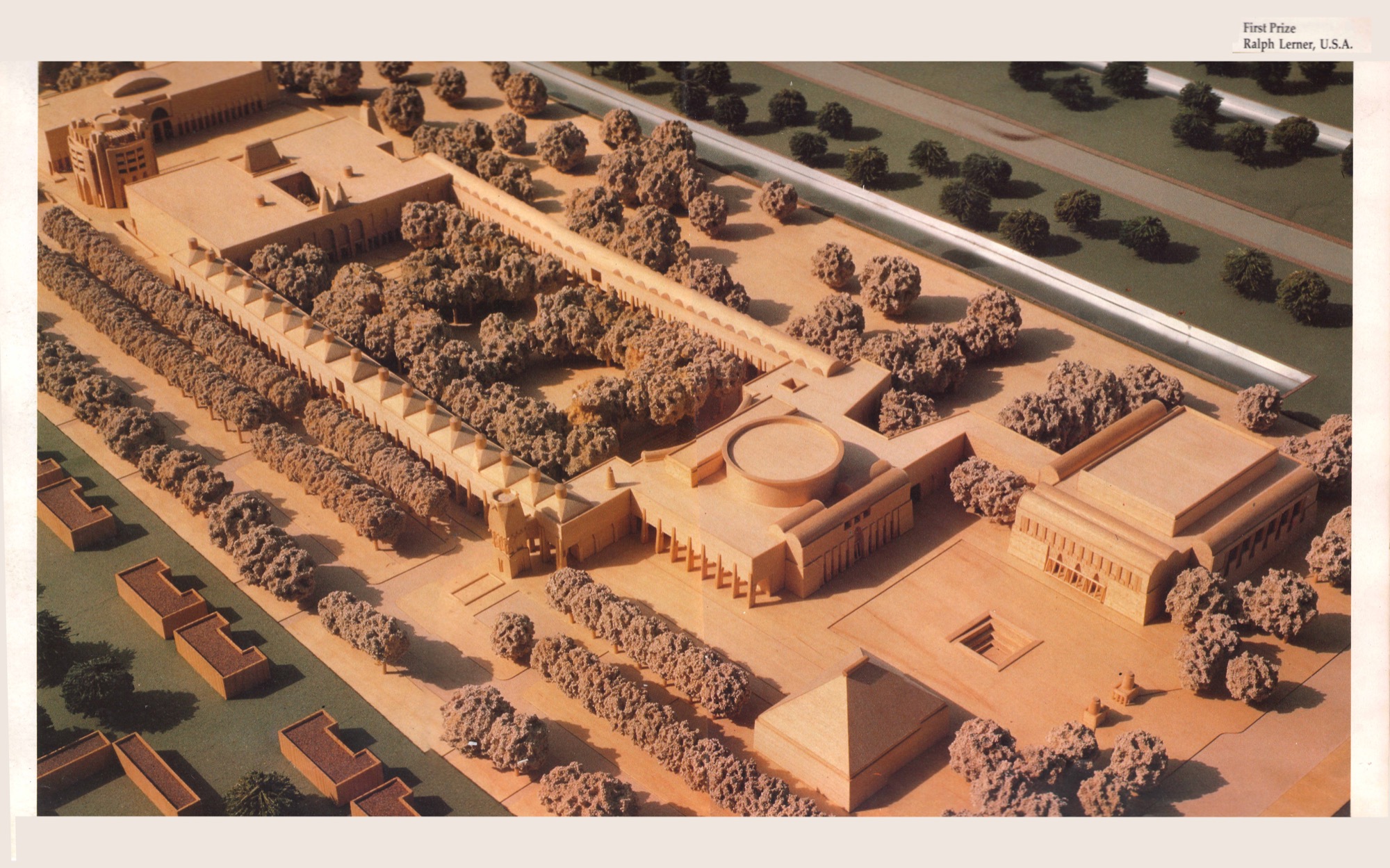

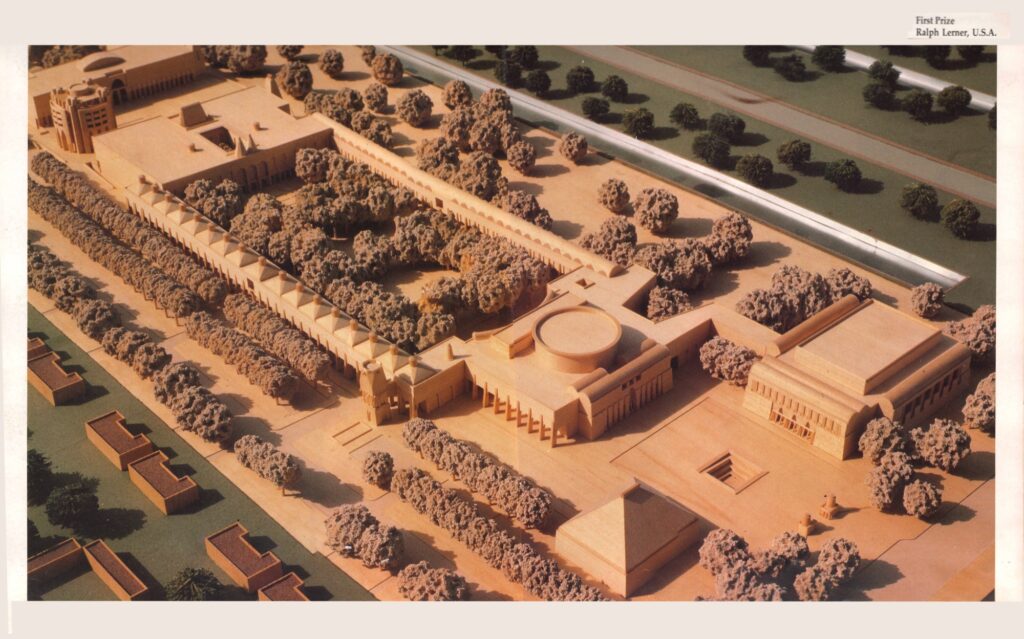

Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, New Delhi was one of the earliest competitions organized on a global scale. Held in 1986, a total of 194 design solutions were submitted for assessment; Ralph Lerner’s scheme was unanimously chosen as the winning entry “with the belief of the jury that this design meets all requirements and this proposal when built; will be as significant as the great building achievements of India”.2

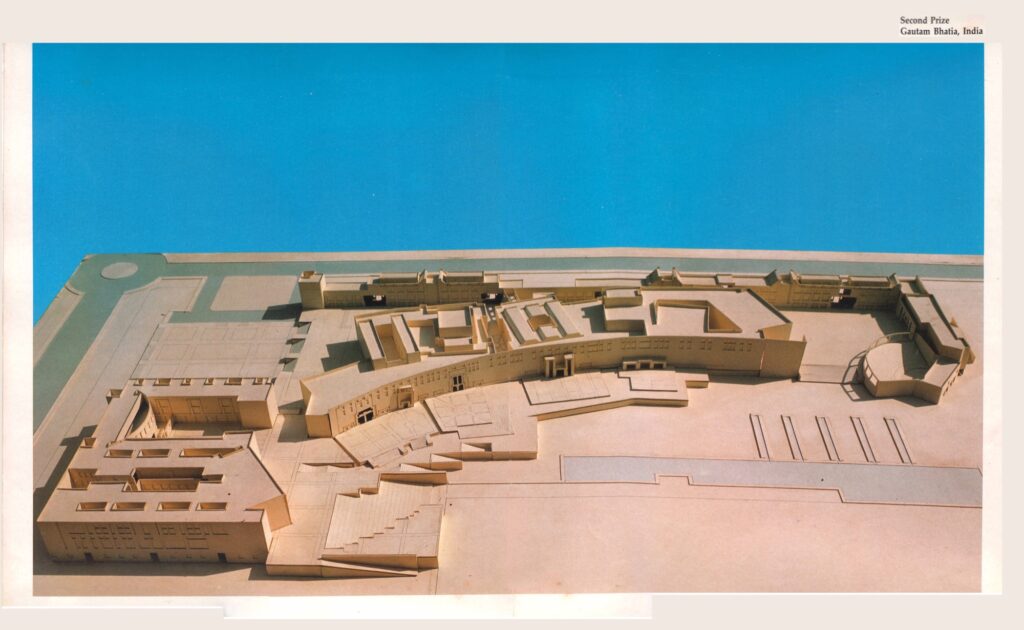

Lerner’s scheme was seeped in the physical and visual context of the colonial city. The runner-up and the consolation prize winners on the other hand were a study in contrast – each one of them reinterpreted the site and its context. This was particularly relevant in conjunction with India’s transition from a colonial to an independent democratic state, as it was no longer relevant to remain compliant with the Imperial city and its power structures.

Speaking of his entry, runner-up Gautam Bhatia stated “the immensity of the building program and its diversity of function had led us to think of the IGNCA as a small city.” He re-imagined the great ceremonial axis, Rajpath, as a river, and the IGNCA as a primordial city on the banks of this river “using the symbols that this implies: the street, the square, the ghats lining the riverfront.” Alluding to a typological metaphor, Bhatia was able to freely dissolve his scheme from its colonial context and place it amidst a new paradigm of post- independent India.

One of the Third-Prize winners, Jourda et Perraudin’s entry from France was a particularly thought-provoking scheme that was much ahead of its time and was conceptualized as “a shelter over the whole site, and the buildings (covered and protected by the Shelter) are the five components of IGNCA”.

Perraudin’s scheme was the most innovative, and the one that deserved to win. He proposed a layer of technology – a parasol suspended above the landscape – that would shade the site and buildings underneath to create a conducive climate for outdoor-indoor to coexist while being sustainable and energy efficient. The scheme demonstrated the ability of the architect to not only re-imagine the brief, but also question its validity. It broke down the Imperial context on all counts, first by rendering the architecture invisible and second by stripping the architecture of any stylistic content. The other Third-Prize winners, David Jeremy Dixon, U.K. and Alexandros Tombazis, Greece presented a similar critical viewpoint through their proposal, which viewed architecture as a cultural construct, not merely a physical or visual one.

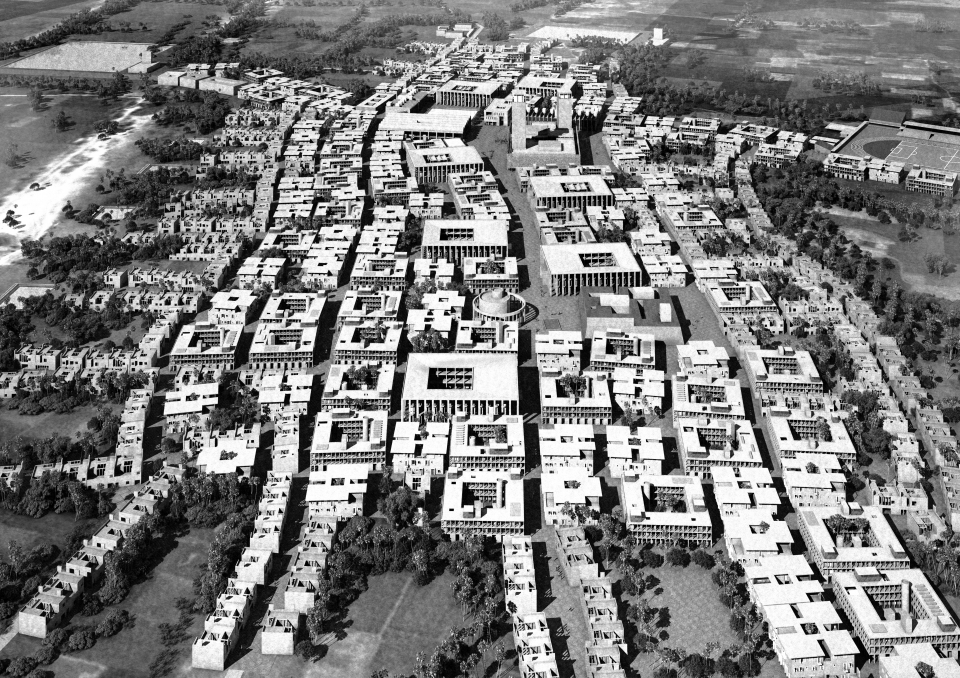

A similar juxtaposition of contextual adaptation versus divergent reinterpretation arose at the design competition for Nalanda University’s Campus Master Plan architectural design 2012. The eight pre-qualified teams comprised the likes of Fumihiko Maki, Allies and Morrison and Snøhetta.

The winning scheme by Vastu Shilpa and that of Hundred Hands + Allies and Morrison were a close match; the former relied heavily on the reinterpretation of the ancient Nalanda Mahavihara to create the modern-day learning campus. Abstracting the “Kalachakra”, a cosmic diagram, to generate a spatial order, the master plan proposed a central lake around which the Academic Hub would be located, with the faculty and student housing zones extending on either side.

The proposal by Hundredhands + Allies and Morrison, on the other hand, set out to transcend current development practices based on land- use segregation, dissolving the binaries such as private-public and residential-academic by creating a fragment of a town where functions and memory coexisted. The entries of Vastu Shilpa and Hundredhands + Allies and Morrison presented contrasting views of place making, with the latter epitomizing the quality of towns and cities where events and public space occurred seamlessly as a continuous urban experience.

In the last twenty years of practice, our firm ABRD Architects has kept busy primarily by competitions – often by winning, but mostly by losing them. Competitions have always fired our imagination – using the opportunity to delve into design charettes. We typically explore divergent options with the intent to question and go beyond the design brief.

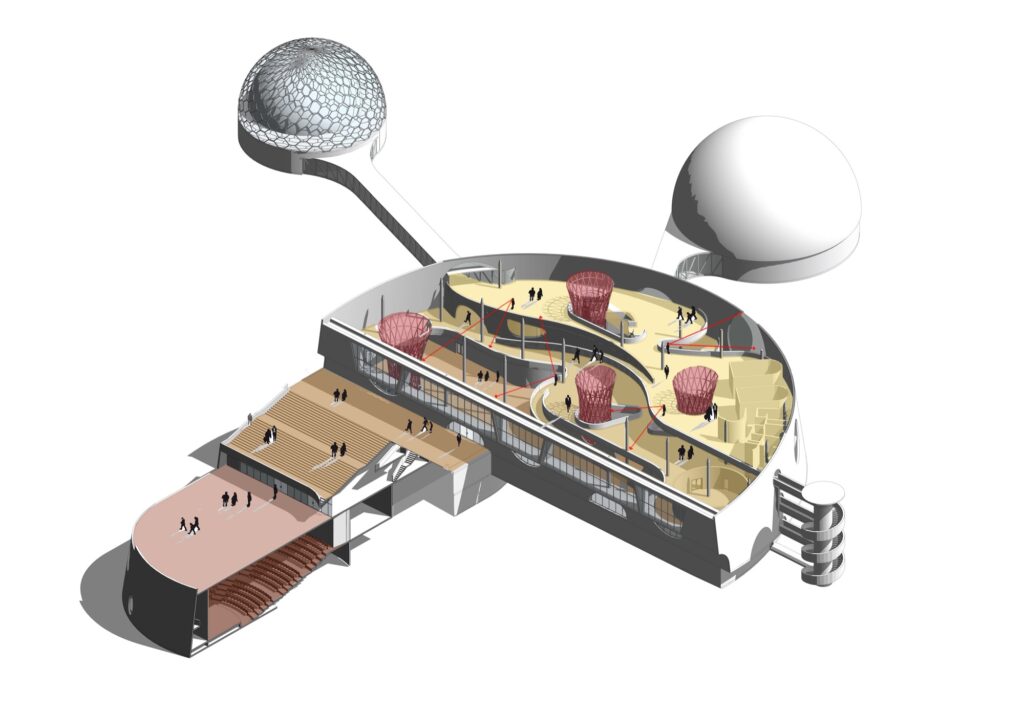

We tasted early success by winning the competition for Alliance Francaise de Delhi at a fairly nascent stage of our practice. Attempting to create an “Image of France and India” together, we construed that the design brief objective was flawed. How could we attempt to have ‘Masala Dosa with French Wine’– in other words, a combination of contrasting architecture styles was not only not feasible but preposterous. Our winning entry focused instead on the French spirit of “bold” combined with the ‘craft’ of the Indian artisan, thus evolving an aesthetic of ‘Hi-Tech’ & ‘Hi-Craft’.

The AFD competition galvanized our young practice, but subsequent success in similar projects like Science City led to the stereotyping of our firm as a “specialist for educational institutions”. Architectural Competitions provided us the opportunity to break the mould of “specialist” by allowing us to explore diverse building types and programmes as well as experiment with varying scales, which private clients seldom did. The commission for National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bangalore and South Asian University, New Delhi – both awarded through competitions – enabled our practice to diversify into a Research and Development building on the one hand, and a complete University Master Plan on the other.

Having done close to twenty-five competitions since, each new competition brings immense enthusiasm in our studio. Acutely aware of the increasing risks in participating in competitions, we nevertheless indulge in order to experiment and energize our team. While we celebrate success at competitions, the losing, unbuilt competition entries retain immense significance for the practice, as they have helped form a great repository of ideas and typologies that we frequently refer to for future projects. We look back at some of our unrealized works with amusement and realize in retrospect that they surely did not deserve to be built. I revisit these projects not only for their spirit of ingenuity and innovation, but also as a constant reminder to question design briefs. The genesis of the design innovation lies in the brief itself, as has also been evident in the IGNCA and Nalanda University projects discussed earlier.

Amongst the numerous unrealized competition projects, our entries for IIT Gandhinagar Students Housing and Science City Guwahati remain constant sources of inspiration. While IIT Gandhinagar Project was significant as a typological reinterpretation, the Science City project enabled our flights of fancy through adopting unconventional curvilinear Geometries, much inspired by science fiction imagery. However, in the span of the last two decades, the nature of competitions has changed dramatically. With increasing politics, strong lobbying by bigger firms and restrictive approach, architects are increasingly becoming ambivalent about entering competitions in India. Emerging winners can bring prestige and business to a firm, but losing can also mean financial loss and profound disappointment after months of effort. Staff members work long days and weekends, and firms rack up bills on everything from models and presentation media to air travel. Some architects have also started to view competitions as exploitative, a way for clients to troll for ideas without committing to a specific architect and compensating them appropriately, as demonstrated by recent competitions for the National War Museum and Amravati.

The harsh reality remains that innovation and the will to create eloquent architecture are no longer on the front seat of decision-making. Reduced to a farcical process, promoters and clients themselves are not committed to the integrity of competitions; one often finds the malaise and apathy extending into the jury panel as well. Devoid of any process to select qualified jury members, competition results often turn out to be absurd, ignoring

basic concerns like ecology, sustainability and constructibility, and reducing the entire process to a mere charade.

While the competition system is in a serious crisis, nobody is sure how to replace it. Unlike some direct commissions, competitions tend to focus on design quality, not political, business or personal connections like “who you golf with.” Moreover, open design competitions in particular foster a culture that motivates professionals towards creating better environments. However great a drain a competition can be on a firm’s finances and personnel, I think architects continue to enjoy the fight. As Eisenmann says – and I couldn’t agree more – “I’m a competitive human being…To me, when I stop getting invited to competitions is when I quit. That’s what makes me alive.3”

Credits: Gautam Bhatia and Ram Sharma

Footnotes:

1. RICE, P. (1998). Peter Rice An Engineer Imagines. New York, Watson-Guptill Publications, Incorporated. pp-25-26

2. Concepts and Responses, International Architectural Design Competition for the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts, New Delhi, pp-34, Mapin Publishing Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad, 1992

3. Robin Pogrebin, Ready, Set, Design: Work as a Contest, https://www.nytimes.com