Preamble

We are obsessed with delivery, with completion, with immediate impact. There is a certain satisfaction that has become addictive. So, what happens when something doesn’t come to fruition?

This turns into an uncomfortable crossroad – something not many are willing to walk on, hence the unbuilt is safely tucked away. It is somewhat of a paradox that our profession is grappling with, amongst many others: the most transformative architectural ideas often remain unbuilt, suspended between vision and reality, waiting for conditions that may never arrive. Yet it is precisely in this liminal space—what Anupama Kundoo calls “a refuge from the built”—that architecture discovers its most radical potential.

This is a conversation on resistance, service, and the power of unbuilt imaginations between Shimul Zaveri Kadri and Anupama Kundoo, renowned established architects, moderated by Khushru Irani, during the launch of the book “Unbuilt 2.0: Architecture of Future Collective”. They offer a perspective on the inherent resistance faced by many visionary ideas, externally and internally. They further delve into architecture beyond the design process—as a test of conviction, where resistance to ideas is what moulds practitioners into becoming experimentalists.

The Long View

“There is resistance to grand visions from inside and from outside. That is very normal in any evolution, that an idea will be met with resistance.”

This observation by Kundoo opens a crucial conversation about the nature of architectural ambition in contemporary practice.

Resistance isn’t simply an obstacle to overcome; it’s the fundamental condition under which meaningful architecture emerges.

Anupama Kundoo has spent decades learning to work with this resistance rather than against it. Her approach embodies what might be called “architectural patience”—a willingness to hold onto difficult visions even when they seem impossible to realise. “The reason why a lot of my things have not also been built and my spirit there is to hold down, hold on and not to give up and say shallow compromise because I want to see it in my lifetime,” she reflects, articulating the profound personal cost of maintaining architectural integrity.

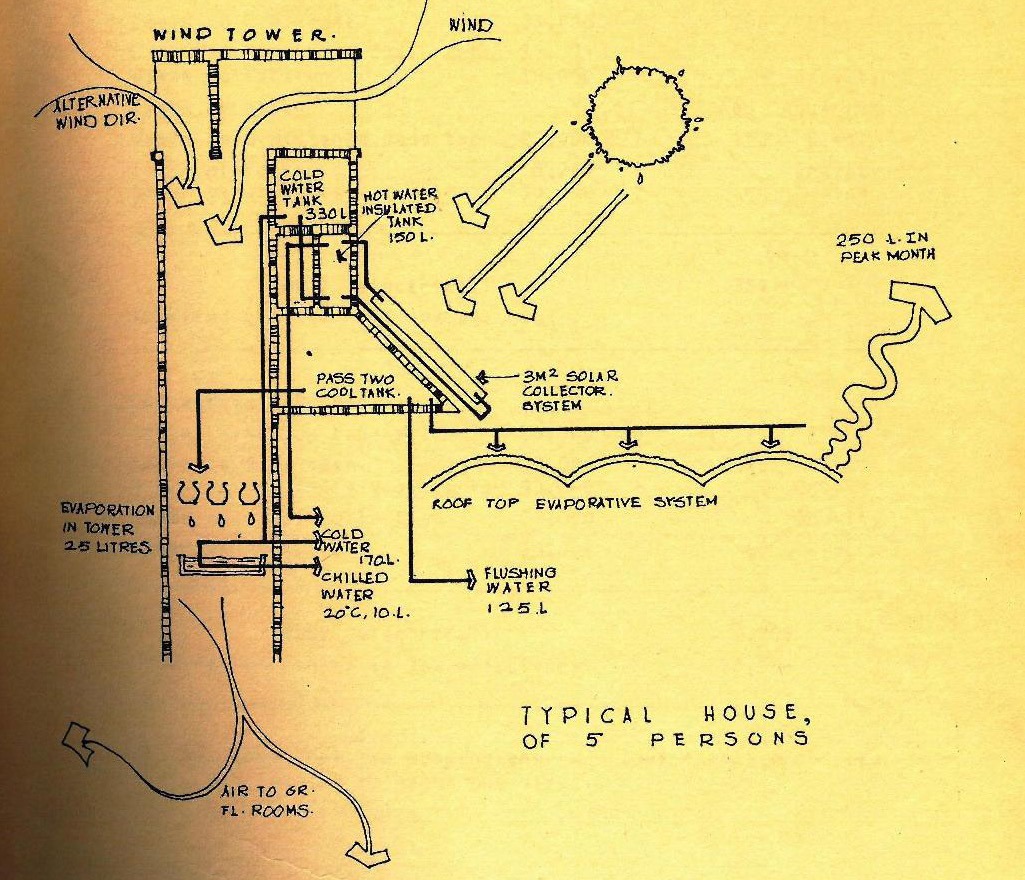

This isn’t romantic idealism. When commissions stall or clients disappear, Kundoo generates alternative forms of production. “I started producing things when my jobs are stuck,” she explains, describing how blocked projects become catalysts for research, experimentation, and prototype development. Her ferrocement research, housing prototypes, and material investigations all emerged from this productive friction between vision and circumstance.

For Kundoo, the building site provides essential nourishment: “The building site nurtures me. So the reason my research develops is because I need the site. I need to feed off that.” This relationship transforms architectural practice from a service profession into something more intimate—a form of sustained conversation between imagination and place that can continue even when conventional construction is impossible.

The question of what architects owe society runs through contemporary practice like a fault line. Shimul Javeri Kadri entered this terrain through personal experience, discovering the failures of municipal education when trying to teach her helper’s daughter English. “I realised that she does not understand a word of what she is being educated on. She’s simply learning by rote,” Kadri recalls, describing a moment that would eventually reshape her practice.

Years later, following her mother-in-law’s death, Kadri found herself “thrown into working on education in BMC schools.” What began as personal involvement became systematic engagement with Mumbai’s educational infrastructure—designing better learning environments while addressing deeper pedagogical problems. Her work extends beyond schools to women’s hostels, daycare centres, and other social infrastructures often ignored by mainstream practice.

This trajectory illustrates what Charles Correa once observed: “We kind of build for the rich and we think for the poor.” Kadri acknowledges this as fundamental to contemporary architectural practice, but she’s found ways to bridge the gap through direct engagement with public institutions and social problems.

Both architects resist the conventional growth model that equates success with office expansion. Kundoo realised early that managing twenty employees meant “doing jobs just to feed those mouths who are hungry, like a mummy bird,” compromising the sincerity essential to her work. Instead, she developed collaborative networks—”decentralised, well, very engaged people”—inspired by beehives where every individual contributes while the larger system organises itself around collective intelligence.

This approach suggests architecture not as an individual genius but as a distributed practice, where influence spreads through collaboration rather than institutional control. “I see very little distance between inner thing and an external thing,” Kundoo explains, describing practice as holistic engagement where professional work, knowledge development, and social sharing form seamless continuity.

India’s urbanisation crisis provides an urgent context for these conversations. “India can’t afford to get its urbanisation wrong,” Kundoo emphasises, drawing from her seventeen-year involvement with Auroville’s city plan. The project’s radical premise—that land belongs to the commons rather than private ownership—challenges fundamental assumptions about urban development and wealth creation.

Most such large-scale visions remain unbuilt, stalled by bureaucratic complexity and competing interests. Yet Kundoo argues this apparent failure conceals deeper success: “The type of projects I’m working on, very large urban projects, it will take years and years because there is a series of negotiations to be patiently had with all kinds of people.”

The unbuilt becomes architecture’s gift to the future—concentrated research into problems that current conditions make difficult to address. “I know many of the things we do will happen maybe even after we are gone,” Kundoo observes, accepting architecture’s temporal nature while maintaining faith in eventual realisation. This requires what she calls “surrender and sacrifice,” not as defeat but as strategic patience.

Critics argue that focusing on large, unlikely projects distracts from immediate problems. But Kundoo counters: “If you have a very big problem and you make yourself so busy with small problems… that’s like a horse with blinkers. I find it very difficult to unsee what I’ve seen.” The unbuilt provides space to maintain systemic vision while engaging with present constraints.

Environmental concerns permeate contemporary architectural discourse, but Kadri approaches climate change from an unexpected angle. “I see climate change as a very fundamental sign of a society… that believes it can control itself, that we can control the environment, we can control each other,” she argues, identifying the problem’s philosophical roots in humanity’s relationship to control and consumption.

This analysis extends to green building certification systems, which Kadri sees as bureaucratic games rather than genuine environmental response. “They wouldn’t give you those 30 points [if] you don’t have air conditioning. There’s a lot of dummy buzzy that goes on with all these manifestos and charters—it sounds fabulous, but it’s a game.”

Her alternative approach emphasises simple strategies: shading, natural ventilation, local materials, and reduced mechanical systems. Describing a resort project, she explains: “We allow all the public spaces to be very, very shaded open air… use natural materials, ensure the wind comes through, ensure that there’s a lot of insulation so that even if you use air conditioning in that room, a very small amount of energy is needed.”

The project’s clay tiles, “made literally on a Potter’s wheel” by “26 villages,” exemplify this approach—environmental response through craft revival and local economic development. Rather than high-tech solutions, Kadri finds beauty and effectiveness in traditional knowledge adapted to contemporary needs.

Are architects overburdened with responsibility for solving society’s problems?

Kadri offers a surprising response: “I prefer the word joy to responsibility in solving that problem.” It is a kind of reframing that can transform architectural engagement from external obligation to internal motivation. Maybe, sustainable practice emerges from genuine pleasure in spatial problem-solving rather than dutiful compliance with social expectations.

The conversation concludes with recognition that “any binary viewing of the world as a win or a loss or a good or a bad is highly problematic. Everything is like, you know, life is in the greys.” This acceptance of complexity becomes not relativistic confusion but sophisticated navigation of contradictory demands, competing values, and uncertain outcomes.

The conversation’s conclusion—”any binary viewing of the world as a win or a loss or a good or a bad is highly problematic. Everything is like, you know, life is in the greys”—positions architectural judgment within complexity rather than certainty. This greyness becomes not relativistic confusion but sophisticated navigation of contradictory demands, competing values, and uncertain outcomes.

For architectural practice, this suggests an ethics of nuanced engagement rather than ideological purity—practice that can work simultaneously within and against existing systems while maintaining commitment to a transformative vision.

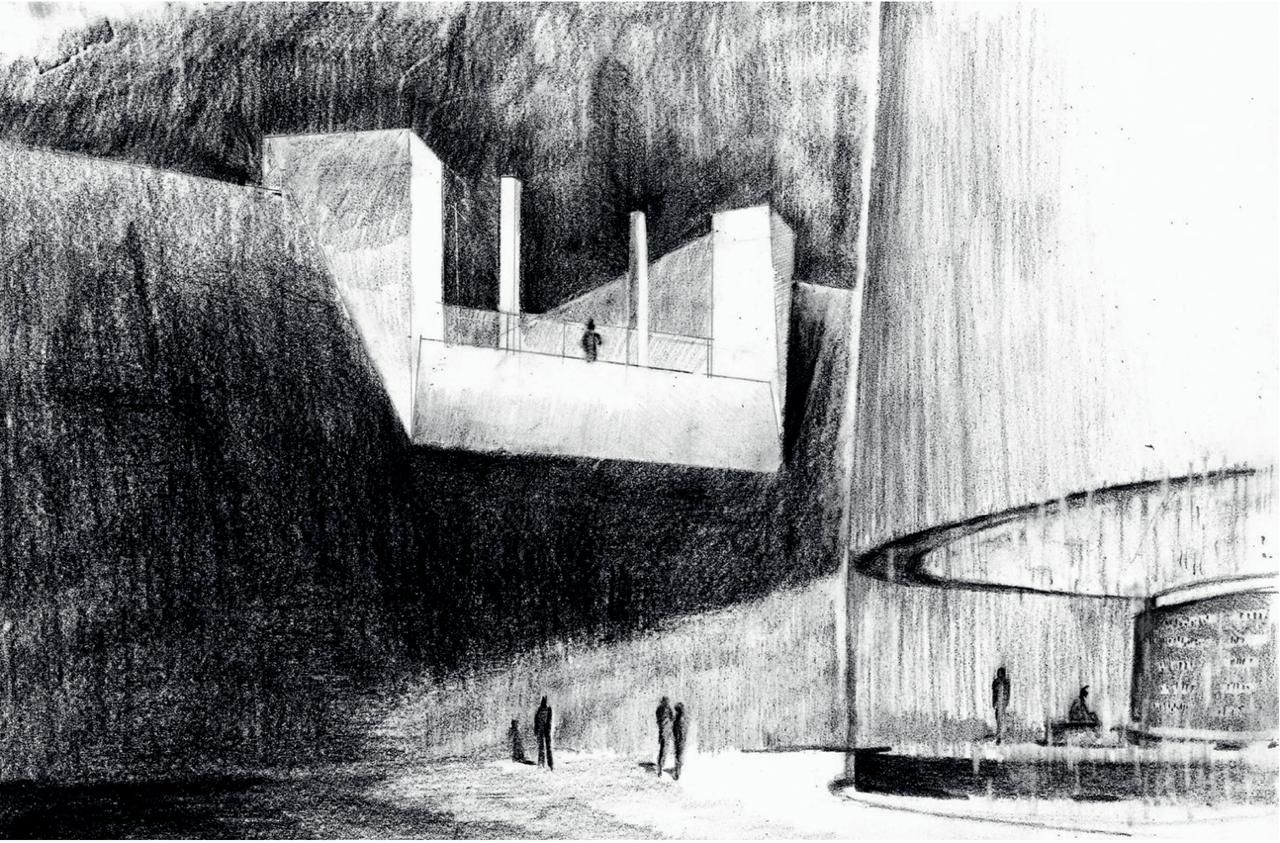

The conversation reveals the unbuilt not as an architectural failure but as a necessary repository of future possibility. These suspended projects function as what we might term “architectural seeds”—concentrated packages of spatial intelligence awaiting appropriate conditions for germination.

Kundoo’s willingness to “dedicate… when the imagination is so grand that one person’s lifetime… won’t be enough to carry it” suggests architecture as a transgenerational practice, where individual careers become moments within longer historical trajectories.

This temporal architecture requires what the conversation terms “surrender and sacrifice”—not defeat but strategic suspension of immediate satisfaction in service of longer-term transformation. The unbuilt becomes architecture’s gift to the future, a form of spatial inheritance that maintains possibility within impossibility.

The architects’ gratitude toward their moderator for “orchestrating it like this, you know, like this magician putting everybody together” suggests that architectural thinking itself requires careful cultivation—spaces of reflection that allow practitioners to “understand practice not just as implementation, but as imagination, service, and thought.”

In this understanding, the unbuilt emerges not as architecture’s shadow but as its most essential dimension—the space where architectural imagination maintains its capacity to exceed present limitations and engage with futures that remain, for now, suspended in the patient territory of the not-yet-built.

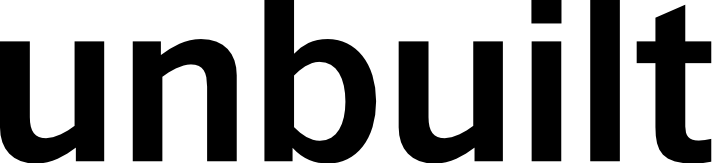

Feature image: National War Memorial. © Sudipto Ghosh, Riyaz Tayyibji

Watch the conversation here:

![Dune (unreleased film) H. R. Giger - [the strange power of unseen films]. Source Wikifandom](https://unbuiltideas.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Dune-unreleased-film-H.-R.-Giger-the-strange-power-of-unseen-films.jpg)